By Brian E. Muhammad, Staff Writer

- December 28, 2021

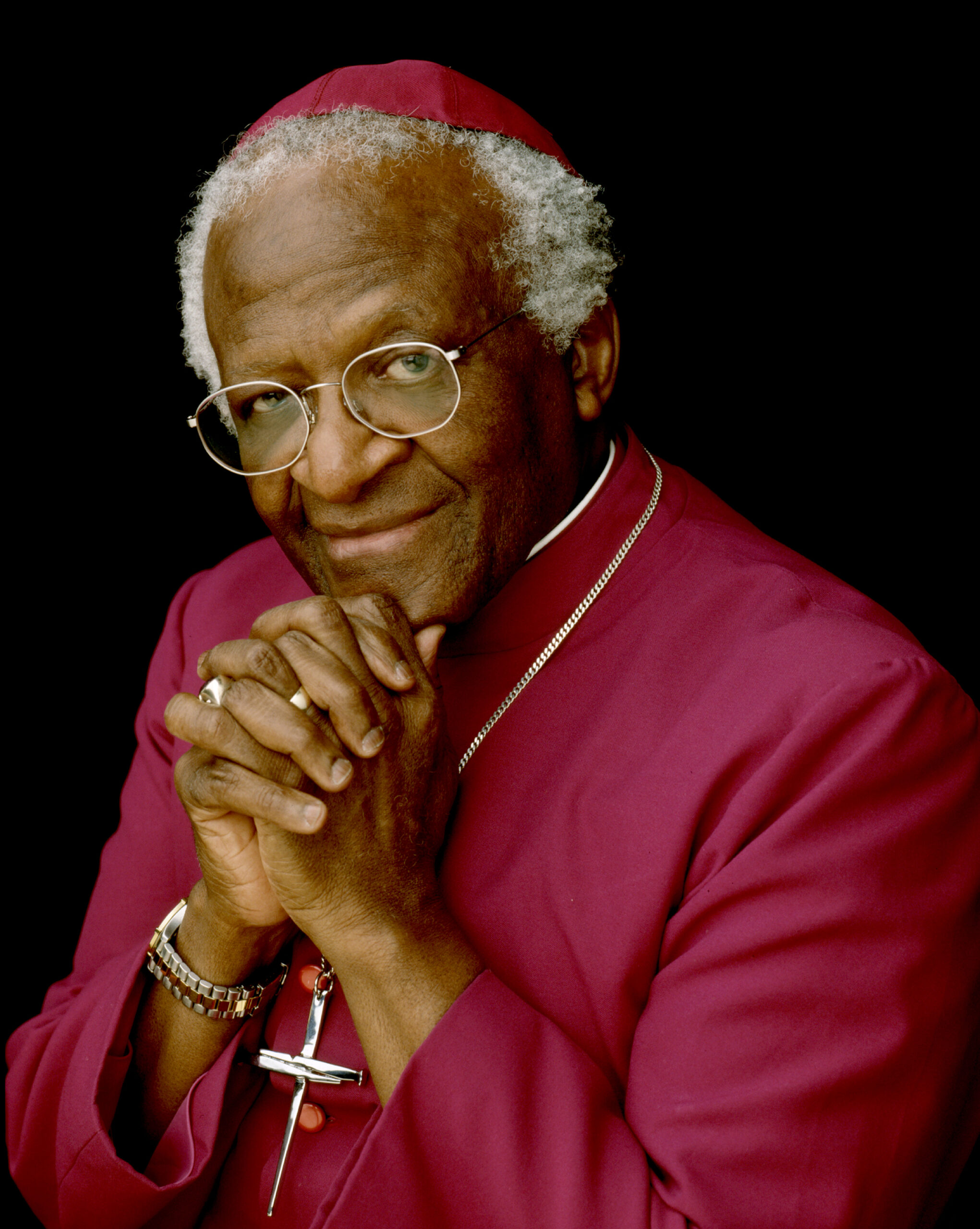

Desmond Tutu (Photo by Deborah Feingold/Corbis via Getty Images)

Desmond Tutu, the champion for human rights and justice worldwide and stalwart of the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa has died. The leader often regarded as the “moral compass” and “voice of integrity” in the country that defeated White minority rule was 90 years old.

The renowned figure lost his battle with prostate cancer which he was diagnosed with in 1997. The official announcement was made by South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa in a statement December 26. He lauded Mr. Tutu as a “patriot without equal” and a leader of principle and pragmatism who remained true to his convictions.

Desmond Tutu, the champion for human rights and justice worldwide and stalwart of the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa has died. The leader often regarded as the “moral compass” and “voice of integrity” in the country that defeated White minority rule was 90 years old.

The renowned figure lost his battle with prostate cancer which he was diagnosed with in 1997. The official announcement was made by South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa in a statement December 26. He lauded Mr. Tutu as a “patriot without equal” and a leader of principle and pragmatism who remained true to his convictions.

Desmond Tutu (Photo by Deborah Feingold/Corbis via Getty Images)

“The passing of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa,” said Mr. Ramaphosa.

He described Mr. Tutu as a man of extraordinary intellect, integrity, and invincibility against the forces of apartheid. But was also “tender and vulnerable” in his compassion for those who suffered oppression, injustice, and violence under apartheid and worldwide. Mr. Ramaphosa announced that all flags will fly half-mast in South Africa and at its diplomatic missions abroad.

“The passing of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa,” said Mr. Ramaphosa.

He described Mr. Tutu as a man of extraordinary intellect, integrity, and invincibility against the forces of apartheid. But was also “tender and vulnerable” in his compassion for those who suffered oppression, injustice, and violence under apartheid and worldwide. Mr. Ramaphosa announced that all flags will fly half-mast in South Africa and at its diplomatic missions abroad.

A weeklong National Day of Mourning was declared, and memorials were planned. For five days his former parish, Saint George Anglican Cathedral is tolling its bell at midday for 10 minutes marking Mr. Tutu’s transition from life into death. The public is honoring the Archbishop with flowers and photos outside the gates of the church, his residences in Cape Town and Soweto, and significant sites of his work.

Mr. Tutu’s body will lie in state Jan.1 at Saint George’s and a requiem mass is scheduled the next day. Mr. Tutu’s body will lie in state Dec. 31 at Saint George’s and a requiem mass is scheduled the next day. Mr. Tutu’s ashes will be buried in a mausoleum within the cathedral. Many remember him as an icon, not only for Africa but the world.

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam issued a statement of reflection on the legacy of Archbishop Tutu and what his life means.

“Although many milestones in the march toward freedom and justice have been reached, the one that ArchbishopTutu wanted most was the same that Dr. Martin Luther King wanted most, to see a genuine brotherhood of the races in a beloved community. Every day that we live we are witnessing new and older efforts to destroy the good that good men like Archbishop Tutu tried to establish,” said Min. Farrakhan. (See page 20-21 for Min. Farrakhan’s statement in its entirety.)

“He was a giant,” said Emira Woods, associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Ms. Woods said Mr. Tutu represented several legacies in his public service. “One of the many legacies… the divestment movement, to push in his leadership under the anti-apartheid era to kind of follow the money,” she recalled.

“He pushed boycott and divestment as a means of bringing the apartheid regime to an end,” Ms. Woods added. She told The Final Call Mr. Tutu proved his brilliance as a strategist and visionary when he seamlessly pushed the same boycott and divestment strategy in the struggle for environmental justice. In 2014 Mr. Tutu lent the power of his stature to fighting the fossil fuel industry, greed, and unfettered exploitation of natural resources.

Ambassadors of the Tygerberg Hospital Children’s Trust, Tutu Tygers, are seen in limited edition T-Shirts, designed by Patta, on the eve of celebrating Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu’s 90th in in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Oct. 6, 2021. Tutu turns 90 on Thursday amid recent racist graffiti on a portrait of the Nobel winner which highlights his continuing relevance of his work for equality. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

With a long legacy of struggle, Mr. Tutu was first and always an Anglican priest who made no secret of his deep dependence on the discipline of prayer, said the Desmond and Leah Tutu Foundation.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born Oct. 7, 1931, in Klerksdorp, west of Johannesburg. He became an educator before entering St. Peter’s Theological College in Rosetenville in 1958. He was ordained in 1961 and in 1966 became chaplain at the University of Fort Hare.

He became bishop of Lesotho, chairman of the South African Council of Churches and, in 1985, the first Black Anglican bishop of Johannesburg. In 1986, Tutu was named the first Black archbishop of Cape Town.

The foundation said his faith “burst the confines” of denomination and religion and embraced all who shared his passion for justice and love. Mr. Tutu spent the closing years of his life increasingly devoted to prayer and contemplation, in the Milnerton home he and his wife shared.

With a long legacy of struggle, Mr. Tutu was first and always an Anglican priest who made no secret of his deep dependence on the discipline of prayer, said the Desmond and Leah Tutu Foundation.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born Oct. 7, 1931, in Klerksdorp, west of Johannesburg. He became an educator before entering St. Peter’s Theological College in Rosetenville in 1958. He was ordained in 1961 and in 1966 became chaplain at the University of Fort Hare.

He became bishop of Lesotho, chairman of the South African Council of Churches and, in 1985, the first Black Anglican bishop of Johannesburg. In 1986, Tutu was named the first Black archbishop of Cape Town.

The foundation said his faith “burst the confines” of denomination and religion and embraced all who shared his passion for justice and love. Mr. Tutu spent the closing years of his life increasingly devoted to prayer and contemplation, in the Milnerton home he and his wife shared.

U.S. Senator for Illinois Barack Obama, left, talks to former Archbishop Desmond Tutu, right, in Cape Town, South Africa, Monday, Aug. 21, 2006. Obama is on a two week African tour which started in Cape Town. (AP Photo/Obed Zilwa)

Father Michael Pfleger of Saint Sabina Church in Chicago told The Final Call that Archbishop Tutu was a consistent voice for freedom. The Chicago activist saw Mr. Tutu as a clergyman unlike many in religion today that sometimes compromise.

“He showed what the religious voice ought to be. All of us in clergy should ask ourselves the question, ‘am I consistent enough to be a voice of freedom?’” said Father Pfleger.

Mr. Tutu didn’t shy from world issues as vast as in Tibet, China, and persecuted Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. He also denounced the war on Iraq. He gave unwavering condemnation to Israel’s oppression of the Palestinian people and likened it to apartheid South Africa.

“I have been to the occupied Palestinian territory,” Mr. Tutu once said. “And I have witnessed the racially segregated roads and housing that reminded me so much of the conditions we experienced in South Africa under the racist system of apartheid,” he said.

CHICAGO – APRIL 4: Civil rights leader Rev. Jesse Jackson (L), Archbishop Desmond Tutu (C) and Minister Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam, attend Palm Sunday mass at St. Sabina’s church where Archbishop Tutu was speaking to the congregation April 4, 2004 in Chicago, Illinois. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Such positions were not taken absent of the myriad of attacks by proponents of Zionism against Mr. Tutu. His name is on a long list of leaders falsely charged with being anti-semitic for just raising the issue of justice.

In a 2002 article Mr. Tutu penned called “Apartheid in the Promised Land,” he pushed back on critics of his principled position. “I am not pro- this people or that. I am pro-justice, pro-freedom. I am anti- injustice, anti-oppression.”

“People are scared in this country [the U.S.], to say wrong is wrong because the Jewish lobby is powerful—very powerful,” argued Mr. Tutu. “Well, so what? For goodness sake, this is God’s world! We live in a moral universe. The apartheid government was very powerful, but today it no longer exists,” he wrote.

A global figure for human rights, Mr. Tutu continued speaking out on a range of ethical and moral issues like illegal arms deals, xenophobia, and HIV/Aids.

As corruption charges and unchanged economic disparity between wealthy elites and an impoverished poor continued in South Africa, Mr. Tutu also became a harsh critic of the ruling African National Congress.

Such positions were not taken absent of the myriad of attacks by proponents of Zionism against Mr. Tutu. His name is on a long list of leaders falsely charged with being anti-semitic for just raising the issue of justice.

In a 2002 article Mr. Tutu penned called “Apartheid in the Promised Land,” he pushed back on critics of his principled position. “I am not pro- this people or that. I am pro-justice, pro-freedom. I am anti- injustice, anti-oppression.”

“People are scared in this country [the U.S.], to say wrong is wrong because the Jewish lobby is powerful—very powerful,” argued Mr. Tutu. “Well, so what? For goodness sake, this is God’s world! We live in a moral universe. The apartheid government was very powerful, but today it no longer exists,” he wrote.

A global figure for human rights, Mr. Tutu continued speaking out on a range of ethical and moral issues like illegal arms deals, xenophobia, and HIV/Aids.

As corruption charges and unchanged economic disparity between wealthy elites and an impoverished poor continued in South Africa, Mr. Tutu also became a harsh critic of the ruling African National Congress.

Flowers are placed alongside a photo of Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, South Africa, Sunday, Dec. 26, 2021. South Africa’s president says Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and the retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, has died at the age of 90. (AP Photo)

The world lost a rare change agent who was consistent across the board. “I think it was an unfortunate loss,” said Dr. Gerald Horne, professor of history at the University of Houston.

“Generally speaking, I think historians of various stripes will be kind to Desmond Tutu,” he said.

Mr. Tutu galvanized global support for the anti-apartheid cause. In 1984 he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his activism. By 1994 apartheid came down with the victory of Nelson Mandela in the first democratically held presidential elections of the country,

Mr. Tutu was asked by Mr. Mandela to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, created as a space to uncover the horrors committed during apartheid.

Later along with Mr. Mandela and other former elder statesmen and world leaders, he served in The Elders, an independent group of global leaders working together for peace, justice, and human rights. The group was made up of former presidents and diplomats.

The world lost a rare change agent who was consistent across the board. “I think it was an unfortunate loss,” said Dr. Gerald Horne, professor of history at the University of Houston.

“Generally speaking, I think historians of various stripes will be kind to Desmond Tutu,” he said.

Mr. Tutu galvanized global support for the anti-apartheid cause. In 1984 he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his activism. By 1994 apartheid came down with the victory of Nelson Mandela in the first democratically held presidential elections of the country,

Mr. Tutu was asked by Mr. Mandela to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, created as a space to uncover the horrors committed during apartheid.

Later along with Mr. Mandela and other former elder statesmen and world leaders, he served in The Elders, an independent group of global leaders working together for peace, justice, and human rights. The group was made up of former presidents and diplomats.

South African Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu hugs author Maya Angelou as she delivered a tribute to him at the J. William Fulbright Prize for International Understanding Award Ceremony, Friday, Nov. 21, 2008, at the State Department in Washington. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

“We are all devastated at the loss of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The Elders would not be who they are today without his passion, commitment and keen moral compass. He inspired me to be a ‘prisoner of hope,’” said Mary Robinson, chair of The Elders and former president of Ireland.

For others, losing such a caliber leader brings reflection and gratitude that one like him lived and contributed on the level he did.

“When someone has the kind of life and length of life that Archbishop Desmond Tutu had … thank the Creator of all things for having allowed his presence,” said Bill Fletcher Jr, past president of TransAfrica Forum.

However, it is important to guard against the misconstruing of Mr. Tutu’s legacy, Mr. Fletcher argued. Anytime progressive and radical leaders pass away, the establishment works to tone down their legacies to make them “safe” and acceptable, said Mr. Fletcher.

“We are all devastated at the loss of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The Elders would not be who they are today without his passion, commitment and keen moral compass. He inspired me to be a ‘prisoner of hope,’” said Mary Robinson, chair of The Elders and former president of Ireland.

For others, losing such a caliber leader brings reflection and gratitude that one like him lived and contributed on the level he did.

“When someone has the kind of life and length of life that Archbishop Desmond Tutu had … thank the Creator of all things for having allowed his presence,” said Bill Fletcher Jr, past president of TransAfrica Forum.

However, it is important to guard against the misconstruing of Mr. Tutu’s legacy, Mr. Fletcher argued. Anytime progressive and radical leaders pass away, the establishment works to tone down their legacies to make them “safe” and acceptable, said Mr. Fletcher.

Former South African President Nelson Mandela, right, reacts with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, left, during the launch of a Walter and Albertina Sisulu exhibition, called, ‘Parenting a Nation’, at the Nelson Mandela Foundation in Johannesburg, South Africa, Wednesday, March 12, 2008. (AP Photo/Themba Hadebe)

“We saw that with (Martin Luther) King,” he said. After he was assassinated, many people didn’t understand the militancy and radicalism of Dr. King because of a watered-down narrative explaining his significance.

Mr. Fletcher expects the same will be attempted with Mr. Tutu, particularly his internationalism and stance on Palestine. “You can’t ignore Tutu … but what the larger establishment can do is rewrite it and blur out significant features,” he said.

Bishop Desmond Tutu is survived by his wife of 66 years, Leah, and their four children.

Final Call Staff Writer Tariqah Muhammad contributed to this report.

“We saw that with (Martin Luther) King,” he said. After he was assassinated, many people didn’t understand the militancy and radicalism of Dr. King because of a watered-down narrative explaining his significance.

Mr. Fletcher expects the same will be attempted with Mr. Tutu, particularly his internationalism and stance on Palestine. “You can’t ignore Tutu … but what the larger establishment can do is rewrite it and blur out significant features,” he said.

Bishop Desmond Tutu is survived by his wife of 66 years, Leah, and their four children.

Final Call Staff Writer Tariqah Muhammad contributed to this report.

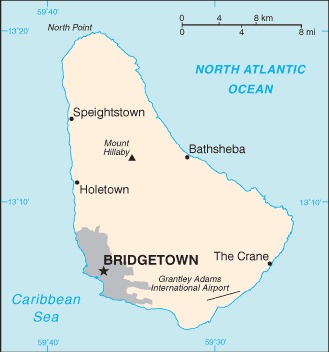

Barbados’ new President Sandra Mason, center right, awards Prince Charles with the Order of Freedom of Barbados during the presidential inauguration ceremony in Bridgetown, Barbados on Tuesday Nov. 30, 2021. Barbados stopped pledging allegiance to Queen Elizabeth II on Tuesday as it shed another vestige of its colonial past and became a republic for the first time in history.(AP Photo / David McD Crichlow)

Barbados’ new President Sandra Mason, center right, awards Prince Charles with the Order of Freedom of Barbados during the presidential inauguration ceremony in Bridgetown, Barbados on Tuesday Nov. 30, 2021. Barbados stopped pledging allegiance to Queen Elizabeth II on Tuesday as it shed another vestige of its colonial past and became a republic for the first time in history.(AP Photo / David McD Crichlow)