BY BRIAN E. MUHAMMAD STAFF WRITER @GLOBALPEEKS

Since high profile police killings of Blacks sparked national unrest in cities across America, there have been loud demands for overhauling policing and radical change in how law enforcement operates.

According to the watchdog group Mapping Police Violence, 1,098 people were slain by police in 2019. Although Blacks only make up 13 percent of the U.S. population, they were 24 percent of those killed, three times more likely than Whites to have a fatal encounter with law enforcement and more likely to be unarmed.

Now comes a backlash against critics and demands for change as powerful, caustic, and unapologetic police unions and their members strike back. Whether harsh words, political pressure, media campaigns or failure to come to work, the boys in blue aren’t going down without a vicious fight.

“For us to expect them to be accommodating … to recognize and understand, that will be almost like a fool’s paradise,” said Hamid Khan, director of Stop LAPD Spying, a grassroots anti-surveillance watchdog group in Los Angeles.

Much of the desired reform goes diametrically opposite the invested interests of police unions, Mr. Khan reasoned.

Critics say police unions have historically declared war over any firings or arrests of cops for wrongdoing or abusive conduct—and police unions have always flouted calls for accountability.

A reform activist and former police officer told The Final Call infractions have gone unpunished and reform have always been blocked because of the inordinate power and influence of police unions along with a justice system culture that doesn’t convict cops.

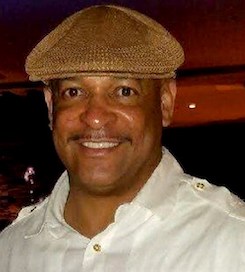

“The culture of police has to be addressed; the police unions have to be addressed. It is not going to go away by itself,” said Ron Hampton, retired Washington, D.C., police officer and former executive director of the National Black Police Association.

Mr. Hampton said police unions represent a serious obstacle to change. Unions wield too much influence outside of their scope, which is to protect officers and offer them legal assistance, he said.

“The police union shouldn’t be telling the police department what it can do or what it can’t do,” said Mr. Hampton.

Where an officer does wrong, he is entitled to his day in court and representation, but he is not entitled to be automatically pardoned and not held accountable when wrong, he continued.

“The unions have been an obstacle to the issue of accountability (and) transparency,” said Mr. Hampton, who led a group that has been a leading voice for fair policing and ending systemic racism in police departments.

How unions got powerful

Over the years, there has been a fall in union membership among many professions and industries, but police union membership has not declined, and unions are strong economically. Unions spend millions lobbying local and state governments to make sure officers have major protections and battle anything they see as a threat.

Financial contributions, fears of appearing soft on crime or labeled an enemy of cops often make politicians reluctant to speak strongly against police officers—even when they are wrong.

“Their lobbying goes very deep,” added Mr. Khan. “It’s not only related to the money, but it’s also about messaging and how they’re going to literally make or break political players,” he said.

Through collective bargaining, policies were built in police contracts that allowed a blue impunity where cops became untouchable, said activists and reform advocates.

A legal tool often used is “qualified immunity” which shields cops from personal liability and lawsuits for excessive force and other infractions in the line of duty. The law is a tool lawmakers are debating and some want eliminated as part of police reforms. Critics say the law helps maintain a “hands off police” culture cops have enjoyed and shields them from the consequences of their actions, including killing people.

A mid-June statement from a group of House Democrats, who recently passed a bill calling for police reform at the federal level, said, “It is long past time to remove this arbitrary and unlawful barrier and to ensure police are held accountable when they violate the constitutional rights of the people whom they are meant to serve.”

Out-of-control police are also costly: According to 2019 data, legal claims against police in America’s largest cities cost taxpayers over $300 million. Advocates say money defending police officers and payouts for lawsuits against cities for police abuses don’t come out of police budgets. The money comes from already financially strapped local governments, they note.

“Money for litigating these cases; that’s money out of the city’s coffers,” said Jennvine Wong, staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society’s Cop Accountability Project in New York.

Atty. Wong told The Final Call, through the city budget, taxpayers are also paying the tab of costly settlements in police misconduct cases.

It’s a domino effect where some cities have to borrow money to pay for civil judgments incurred from police wrongdoing on city time.

In addition to litigation and settlements costs, Atty. Wong said many officers are still able to collect six-figure salaries while under suspension or on modified duty—in some cases for years.

“That’s a lot of money … we are throwing at the police and essentially its going into the black hole of misconduct,” Atty. Wong added.

Analysis from the Urban Institute said between 1977 and 2017 the cost of U.S. policing ballooned from $42.3 billion to $114.5 billion per year.

The money spent, brutal and deadly actions for cops and no consequences have helped feed calls to defund police, or take money away from police departments and use it for things like mental health first responders and other approaches that would lessen encounters with cops.

Public perceptions of cops

Polls show a weariness with police behavior and dramatic shifts of opinion about policing and race. An Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll found more Americans compared to five years ago believe police brutality is a serious problem that too often goes undisciplined and unequally targets Blacks.

The poll said more than two-thirds of the public agree the criminal justice system needs either major changes or a complete overhaul. Blacks are more likely than Whites to advocate a complete transformation. The poll said overall, 48 percent of Americans say police violence against the public is a serious problem, up from 32 percent in 2015.

That year, only 19 percent of Whites said police violence against civilians was an extreme or serious problem; now 39 percent say the same.

The survey was conducted after weeks of mass anti-police violence protests and calls by politicians and activists to “defund” police departments.

The National Black Police Association said systemic racism within police departments and the devaluing of Black life is the crux of the problem.

“The DNA of law enforcement is to send a message of fear to Black residents that creates a kind of psychological distress,” said Damon K. Jones of the National Black Police Association.

Mr. Jones said Black police professionals spent years demanding legislation and policies for police oversight.

“We recognize the pain of our communities; we are four degrees of separation,” he said in an open statement to elected officials. “We know the victim, we know someone who knows the victim; the victim is a family member, and in many cases even as Black law enforcement, we are the victim.”

What unions are protecting

According to the watchdog group Mapping Police Violence, 1,098 people were slain by police in 2019. Although Blacks only make up 13 percent of the U.S. population, they were 24 percent of those killed, three times more likely than Whites to have a fatal encounter with law enforcement and more likely to be unarmed. Mapping Police Violence also pointed out that 99 percent of killings by police from 2013-2019 have not resulted in officers being charged with a crime.

The low prosecution rate has a lot to do with the influence of police unions and laws that favor police—it is also driving calls for change.

The videotaped death of George Floyd, 46, a Black man who lost his life May 25 in the custody of Minneapolis cops, sparked global outrage. Weeks later an Atlanta officer fatally shot 27-year-old Rayshard Brooks in the back as he ran away in a Wendy’s parking lot. Cops involved in both cases were charged.

In Oregon, an officer lost his job and then returned to work after fatally shooting an unarmed Black man in the back. A Florida sergeant was let go six times for using excessive force and stealing from suspects, while a Texas lieutenant was terminated five times after being accused of striking two women, making threatening calls and committing other infractions, according to the Associated Press.

These officers were fired but rehired after an arbitrator reversed the decision.

This illustrates how police unions stand in the way of accountability, said experts.

“Arbitration inherently undermines police decisions,” said Michael Gennaco, a police reform expert and former federal civil rights prosecutor who specialized in police misconduct cases. “It’s dismaying to see arbitrators regularly putting people back to work,” he told the Associated Press.

“Change must come now,” declared California Democrat Maxine Waters in a June 21 statement after Andres Guardado, 18, was shot by a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy.

For weeks, the American people and the world have marched to demand accountability, and an end to aggressive and violent police tactics, said the outspoken Black lawmaker.

“We will not stand for it, whether it is in Atlanta, or like this case, in South Los Angeles,” vowed Rep. Waters.

Union heads and law enforcement defenders blame politicians and government for the social conditions that produce problems. Politicians and city officials talk about reform but have sided with “protesters,” “anarchists,” and “law breakers,” they complain, including President Donald Trump.

Some things have changed recently with cops fired, arrested, and charged with misconduct, such as using an outlawed chokehold in New York and abusing anti-police brutality protestors.

Neither union leaders, nor many cops are happy about the scrutiny.

In Wilmington, N.C., three White cops were fired after being heard over squad car video discussing “slaughtering n****rs” and calling for a new Civil War. Each blamed stress from an “anti-cop” climate as a reason for their “venting.” (See story page 3.)

In Atlanta, many cops refused to come to work and after two officers were charged in the Brooks killing, they called in sick. Philadelphia cops threatened to get the “blue flu” over suspensions of two of their own for abusing demonstrators.

In New York, text messages circulated about an impending NYPD refusal to work on July 4 “to let the city have their independence without cops,” reported the New York Post.

“Over the past few weeks, we have been attacked in the streets, demonized in the media and denigrated by practically every politician in this city,” railed Patrick Lynch, president of the Police Benevolent Association, in the article.

Mr. Lynch complained cops were unappreciated and abandoned.

“Now we are facing the possibility of being arrested any time we go out to do our job,” Mr. Lynch said.

Heavy violence in Chicago made national headlines but calls for “blue flu” over the July 4 weekend did not. The local CBS News affiliate reported June 22 “a new push by members of the police union to get officers on the street to stand down—and even stay home.” According to CBS 2, the move started with a text message about the need to send Mayor Lori Lightfoot and the City Council a message. “ ‘The FOP Lodge 7 cannot advocate for it because of the contract,’ the text message reads. But, it adds, ‘individual officers can,’ ” CBS 2 reported. The Fraternal Order of Police president didn’t authorize the move but didn’t necessarily oppose it, CBS 2 added.

“When something stupid like that happens to basically tell officers to abandon their post, that is the height of dereliction of duty,” said Mayor Lightfoot.

But despite the union threats some cities and states, feeling the pressure of protests have changed some policies.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed an executive order making N.Y. police disciplinary records public after decades of secrecy.

“We’re not going to be as a state government subsidizing improper police tactics. We’re not doing it,” Gov. Cuomo said. “And this is how we’re going to do it.”

The order also requires the roughly 500 police departments across the Empire State to develop a plan by April 1, 2021 to address systemic racism in their ranks. If a department refuses to comply Gov. Cuomo threatens to strip it of state funding.

“This is a historic win for New York and a long overdue change to the most restrictive police secrecy law in the country,” said Donna Lieberman of the American Civil Liberties Union.

The change was the result of years of work led by families whose loved ones were killed by police and who were routinely rebuffed while trying to find out what the department was doing about holding officers accountable.

Problematic police culture

A blue wall of silence permeates departments where cops look the other way from bad behavior permitting wrongdoing to go unchecked.

This permitted ex-cop Derek Chauvin, who kneeled on the neck of George Floyd for almost nine minutes, to keep working despite an extensive record of complaints spanning 19 years as a cop.

Former College Park, Ga., police chief Ron Fears said that culture dominates and influences cops who “stand by silently,” “do nothing” or even participate in wrongdoing.

“They’re not going to change things until the leadership from the very top says we’re not going to stand for that,” Mr. Fears said. Law enforcement is not there yet, he said.

Asked about Black officers challenging the culture, Mr. Fears wasn’t optimistic. “I think the culture is one where Black officers don’t step out and stand up because if you do, there is a price to pay,” he said.

(Final Call staff contributed to this report.)

Now comes a backlash against critics and demands for change as powerful, caustic, and unapologetic police unions and their members strike back. Whether harsh words, political pressure, media campaigns or failure to come to work, the boys in blue aren’t going down without a vicious fight.

“For us to expect them to be accommodating … to recognize and understand, that will be almost like a fool’s paradise,” said Hamid Khan, director of Stop LAPD Spying, a grassroots anti-surveillance watchdog group in Los Angeles.

Much of the desired reform goes diametrically opposite the invested interests of police unions, Mr. Khan reasoned.

Critics say police unions have historically declared war over any firings or arrests of cops for wrongdoing or abusive conduct—and police unions have always flouted calls for accountability.

A reform activist and former police officer told The Final Call infractions have gone unpunished and reform have always been blocked because of the inordinate power and influence of police unions along with a justice system culture that doesn’t convict cops.

“The culture of police has to be addressed; the police unions have to be addressed. It is not going to go away by itself,” said Ron Hampton, retired Washington, D.C., police officer and former executive director of the National Black Police Association.

Mr. Hampton said police unions represent a serious obstacle to change. Unions wield too much influence outside of their scope, which is to protect officers and offer them legal assistance, he said.

“The police union shouldn’t be telling the police department what it can do or what it can’t do,” said Mr. Hampton.

Where an officer does wrong, he is entitled to his day in court and representation, but he is not entitled to be automatically pardoned and not held accountable when wrong, he continued.

“The unions have been an obstacle to the issue of accountability (and) transparency,” said Mr. Hampton, who led a group that has been a leading voice for fair policing and ending systemic racism in police departments.

How unions got powerful

Over the years, there has been a fall in union membership among many professions and industries, but police union membership has not declined, and unions are strong economically. Unions spend millions lobbying local and state governments to make sure officers have major protections and battle anything they see as a threat.

Financial contributions, fears of appearing soft on crime or labeled an enemy of cops often make politicians reluctant to speak strongly against police officers—even when they are wrong.

“Their lobbying goes very deep,” added Mr. Khan. “It’s not only related to the money, but it’s also about messaging and how they’re going to literally make or break political players,” he said.

Through collective bargaining, policies were built in police contracts that allowed a blue impunity where cops became untouchable, said activists and reform advocates.

A legal tool often used is “qualified immunity” which shields cops from personal liability and lawsuits for excessive force and other infractions in the line of duty. The law is a tool lawmakers are debating and some want eliminated as part of police reforms. Critics say the law helps maintain a “hands off police” culture cops have enjoyed and shields them from the consequences of their actions, including killing people.

A mid-June statement from a group of House Democrats, who recently passed a bill calling for police reform at the federal level, said, “It is long past time to remove this arbitrary and unlawful barrier and to ensure police are held accountable when they violate the constitutional rights of the people whom they are meant to serve.”

Out-of-control police are also costly: According to 2019 data, legal claims against police in America’s largest cities cost taxpayers over $300 million. Advocates say money defending police officers and payouts for lawsuits against cities for police abuses don’t come out of police budgets. The money comes from already financially strapped local governments, they note.

“Money for litigating these cases; that’s money out of the city’s coffers,” said Jennvine Wong, staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society’s Cop Accountability Project in New York.

Atty. Wong told The Final Call, through the city budget, taxpayers are also paying the tab of costly settlements in police misconduct cases.

It’s a domino effect where some cities have to borrow money to pay for civil judgments incurred from police wrongdoing on city time.

In addition to litigation and settlements costs, Atty. Wong said many officers are still able to collect six-figure salaries while under suspension or on modified duty—in some cases for years.

“That’s a lot of money … we are throwing at the police and essentially its going into the black hole of misconduct,” Atty. Wong added.

Analysis from the Urban Institute said between 1977 and 2017 the cost of U.S. policing ballooned from $42.3 billion to $114.5 billion per year.

The money spent, brutal and deadly actions for cops and no consequences have helped feed calls to defund police, or take money away from police departments and use it for things like mental health first responders and other approaches that would lessen encounters with cops.

Public perceptions of cops

Polls show a weariness with police behavior and dramatic shifts of opinion about policing and race. An Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll found more Americans compared to five years ago believe police brutality is a serious problem that too often goes undisciplined and unequally targets Blacks.

The poll said more than two-thirds of the public agree the criminal justice system needs either major changes or a complete overhaul. Blacks are more likely than Whites to advocate a complete transformation. The poll said overall, 48 percent of Americans say police violence against the public is a serious problem, up from 32 percent in 2015.

That year, only 19 percent of Whites said police violence against civilians was an extreme or serious problem; now 39 percent say the same.

The survey was conducted after weeks of mass anti-police violence protests and calls by politicians and activists to “defund” police departments.

The National Black Police Association said systemic racism within police departments and the devaluing of Black life is the crux of the problem.

“The DNA of law enforcement is to send a message of fear to Black residents that creates a kind of psychological distress,” said Damon K. Jones of the National Black Police Association.

Mr. Jones said Black police professionals spent years demanding legislation and policies for police oversight.

“We recognize the pain of our communities; we are four degrees of separation,” he said in an open statement to elected officials. “We know the victim, we know someone who knows the victim; the victim is a family member, and in many cases even as Black law enforcement, we are the victim.”

What unions are protecting

According to the watchdog group Mapping Police Violence, 1,098 people were slain by police in 2019. Although Blacks only make up 13 percent of the U.S. population, they were 24 percent of those killed, three times more likely than Whites to have a fatal encounter with law enforcement and more likely to be unarmed. Mapping Police Violence also pointed out that 99 percent of killings by police from 2013-2019 have not resulted in officers being charged with a crime.

The low prosecution rate has a lot to do with the influence of police unions and laws that favor police—it is also driving calls for change.

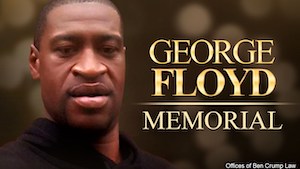

The videotaped death of George Floyd, 46, a Black man who lost his life May 25 in the custody of Minneapolis cops, sparked global outrage. Weeks later an Atlanta officer fatally shot 27-year-old Rayshard Brooks in the back as he ran away in a Wendy’s parking lot. Cops involved in both cases were charged.

In Oregon, an officer lost his job and then returned to work after fatally shooting an unarmed Black man in the back. A Florida sergeant was let go six times for using excessive force and stealing from suspects, while a Texas lieutenant was terminated five times after being accused of striking two women, making threatening calls and committing other infractions, according to the Associated Press.

These officers were fired but rehired after an arbitrator reversed the decision.

This illustrates how police unions stand in the way of accountability, said experts.

“Arbitration inherently undermines police decisions,” said Michael Gennaco, a police reform expert and former federal civil rights prosecutor who specialized in police misconduct cases. “It’s dismaying to see arbitrators regularly putting people back to work,” he told the Associated Press.

“Change must come now,” declared California Democrat Maxine Waters in a June 21 statement after Andres Guardado, 18, was shot by a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy.

For weeks, the American people and the world have marched to demand accountability, and an end to aggressive and violent police tactics, said the outspoken Black lawmaker.

“We will not stand for it, whether it is in Atlanta, or like this case, in South Los Angeles,” vowed Rep. Waters.

Union heads and law enforcement defenders blame politicians and government for the social conditions that produce problems. Politicians and city officials talk about reform but have sided with “protesters,” “anarchists,” and “law breakers,” they complain, including President Donald Trump.

Some things have changed recently with cops fired, arrested, and charged with misconduct, such as using an outlawed chokehold in New York and abusing anti-police brutality protestors.

Neither union leaders, nor many cops are happy about the scrutiny.

In Wilmington, N.C., three White cops were fired after being heard over squad car video discussing “slaughtering n****rs” and calling for a new Civil War. Each blamed stress from an “anti-cop” climate as a reason for their “venting.” (See story page 3.)

In Atlanta, many cops refused to come to work and after two officers were charged in the Brooks killing, they called in sick. Philadelphia cops threatened to get the “blue flu” over suspensions of two of their own for abusing demonstrators.

In New York, text messages circulated about an impending NYPD refusal to work on July 4 “to let the city have their independence without cops,” reported the New York Post.

“Over the past few weeks, we have been attacked in the streets, demonized in the media and denigrated by practically every politician in this city,” railed Patrick Lynch, president of the Police Benevolent Association, in the article.

Mr. Lynch complained cops were unappreciated and abandoned.

“Now we are facing the possibility of being arrested any time we go out to do our job,” Mr. Lynch said.

Heavy violence in Chicago made national headlines but calls for “blue flu” over the July 4 weekend did not. The local CBS News affiliate reported June 22 “a new push by members of the police union to get officers on the street to stand down—and even stay home.” According to CBS 2, the move started with a text message about the need to send Mayor Lori Lightfoot and the City Council a message. “ ‘The FOP Lodge 7 cannot advocate for it because of the contract,’ the text message reads. But, it adds, ‘individual officers can,’ ” CBS 2 reported. The Fraternal Order of Police president didn’t authorize the move but didn’t necessarily oppose it, CBS 2 added.

“When something stupid like that happens to basically tell officers to abandon their post, that is the height of dereliction of duty,” said Mayor Lightfoot.

But despite the union threats some cities and states, feeling the pressure of protests have changed some policies.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed an executive order making N.Y. police disciplinary records public after decades of secrecy.

“We’re not going to be as a state government subsidizing improper police tactics. We’re not doing it,” Gov. Cuomo said. “And this is how we’re going to do it.”

The order also requires the roughly 500 police departments across the Empire State to develop a plan by April 1, 2021 to address systemic racism in their ranks. If a department refuses to comply Gov. Cuomo threatens to strip it of state funding.

“This is a historic win for New York and a long overdue change to the most restrictive police secrecy law in the country,” said Donna Lieberman of the American Civil Liberties Union.

The change was the result of years of work led by families whose loved ones were killed by police and who were routinely rebuffed while trying to find out what the department was doing about holding officers accountable.

Problematic police culture

A blue wall of silence permeates departments where cops look the other way from bad behavior permitting wrongdoing to go unchecked.

This permitted ex-cop Derek Chauvin, who kneeled on the neck of George Floyd for almost nine minutes, to keep working despite an extensive record of complaints spanning 19 years as a cop.

Former College Park, Ga., police chief Ron Fears said that culture dominates and influences cops who “stand by silently,” “do nothing” or even participate in wrongdoing.

“They’re not going to change things until the leadership from the very top says we’re not going to stand for that,” Mr. Fears said. Law enforcement is not there yet, he said.

Asked about Black officers challenging the culture, Mr. Fears wasn’t optimistic. “I think the culture is one where Black officers don’t step out and stand up because if you do, there is a price to pay,” he said.

(Final Call staff contributed to this report.)