By Bryan 18X Crawford -Contributing Writer-

The biggest talk in the world of college athletics isn’t who the number one team or player is in the country, it’s if the NCAA has finally been stripped of its authoritarian power to prevent student athletes from capitalizing off their name and likeness. It’s the very thing the powerful athletic collegiate governing body has done for years—bringing home billions of dollars in the process and penalizing young men and women for accepting things like meals, or anything of value related to their position as high-profile athletes.

Graphic: Bigstock.com

However, while the “Fair Pay to Play Act” is the latest shockwave to hit the world of college sports, the reality is this fight has been ongoing for more than two decades. And, it all started with something as innocuous as an electronic video game.

California Governor Gavin Newsom may have signed the Fair Pay to Play (Calif. Senate Bill 206) act into law on Sept. 30, but it was former UCLA basketball standout Ed O’Bannon who got the ball rolling in 2009 when he filed a lawsuit against the NCAA and the Collegiate Licensing Company, accusing both of violating the Sherman Antitrust Act. That act regulates competition among enterprises and prevents agreements that lead to anticompetitive conduct. Simply stated, the Sherman Antitrust Act essentially ensures the preservation of a competitive marketplace.

What caused Mr. O’Bannon to put his name and reputation on the line to become the lead plaintiff in a case against a multi-billion-dollar entity?

In 2009, EA Sports released “NCAA Basketball ‘09” which featured the 1995 UCLA National Championship team in which Ed O’Bannon was the star player. All of the players’ heights, weights, positions, jersey numbers and even features mirrored their real-life counterparts. The only difference? There were no names associated with the players, but you knew exactly who they were when you played the game.

“I played basketball at UCLA in the 1990s and loved almost every minute of it. I went on to play in the NBA, but my true passion stayed with college basketball. After a decade in pro hoops, I retired in 2005,” Mr. O’Bannon wrote in a recent op-ed for Sports Illustrated. “A few years later, I saw myself featured in a college basketball video game that sold for $60. I hadn’t asked to be in the game. And no one had offered to pay me, or any other current or former players who were ‘in the game’ as the game’s advertisement boasted,” stated Mr. O’Bannon.

“That experience led to me to bring a lawsuit against the NCAA ... . This wasn’t about money. This was about taking someone’s identity and profiting from it. And it was about changing the rules to not let that happen again,” he added.

Julius Hodge was a highly ranked, highly recruited high school basketball player from Harlem. In 2001, he was a McDonald’s All-American and went on to play collegiately at North Carolina State, and professionally in the NBA and overseas. He too remembers seeing and playing with his own likeness in the game and thinking how someone was making money off him while he never saw a dime.

“I was a sophomore in college playing this video game, and I see myself at 6-7, number 24 in a red jersey, playing in the ACC for NC State. I know that’s me, and I’m not able to monetize that, but I know that someone else can and has, it’s not a good feeling,” Mr. Hodge told The Final Call. “I stopped playing basketball video games because of it and I haven’t since then.”

While this issue of monetizing real people’s likenesses and not paying them for it may have started with video games, it’s reach is much broader. Colleges, universities, and the NCAA rake in millions of dollars in annual revenue from the sale of merchandise made popular by athletes as part of apparel deals they sign with sneaker companies like Nike and Adidas, which sponsors athletic programs and provides athletes with branded products.

Calif. Gov. Newsom signing legislation on new bill on LeBron James’ show “The Shop.” Photo: Youtube

Schools routinely sell on campus and online, jerseys, shirts, hats and other items that have been popularized by star athletes. They keep 100 percent of the profits, giving nothing in return to the athlete whose performance, name recognition and popularity is the reason the item even sold in the first place. But it goes even deeper than merchandise, or even the athlete’s on men’s teams. Women are penalized too.

In 2017, twins Dakota and Dylan Gonzalez were forced to forgo their final year of eligibility at UNLV because under NCAA rules, the sisters wouldn’t be allowed to play basketball, while still pursuing interests such as modeling, music and creating a clothing line, all of which capitalized on their social media popularity, and would’ve paid them as student athletes and members of the UNLV Lady Rebels basketball team.

“For me I think the rules and regulations are 100 percent the reason why we didn’t want to continue to play,” Dylan Gonzalez told the Las Vegas Review-Journal in an interview. “We personally felt like if we would have been able to take on the opportunities outside of basketball, then we would have still continued to commit ourselves to playing for the last year that we had,” she pointed out.

“We are bred and conditioned to believe that college is what’s going to get you ready for that start in your life after school,” Dakota Gonzalez added. “So, as a student-athlete when you feel like you’re being held back from that, where are you really getting an advantage? Because even though I’m getting an education, I don’t have a resume.”

While many people associated with sports at all levels support college athletes being able to monetize their own likenesses the same way the NCAA has for decades, there are many detractors who feel the decision made by California, which is also gaining traction in states like Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Minnesota, Ohio and others, will ruin college sports and the NCAA as we know it.

Tim Tebow was an All-American quarterback at the University of Florida who won the Heisman Trophy and led the Gators to two SEC and NCAA football championships. He was completely against the Fair Pay to Play Act.

“When I was at the University of Florida, I think my jersey was one of the top-selling jerseys around the world. It was like Kobe, LeBron and then I was right behind them. And I didn’t make a dollar from it, but nor did I want to because I knew going into college what it was all about,” Mr. Tebow said on ESPN’s morning sports talk show, “First Take.”

Mr. Tebow was soundly criticized for it, largely based on his upbringing which differs from that of a large percentage of college athletes who drive revenue and don’t come from the same situation as he did. Tim Tebow grew up on a 40-acre farm outside Jacksonville. His parents had a swimming pool in the backyard, a basketball court in the driveway, and they built their son a batting cage because some say he was a better baseball player than quarterback. Mr. Tebow, who is White, was given every opportunity to become an elite athlete; opportunities that athletes from less privileged backgrounds—many who are Black—the same ones fighting to not be pimped by the NCAA system, aren’t afforded, critics argue.

So, what is the harm in allowing college athletes to make money off their likenesses? Mark Emmert, president of the NCAA whose base salary is reportedly over $2 million a year says the bill is an existential threat to the college sports model. But that’s exactly what it was designed to be. Making 100 percent of the profits off the hard work and sweat of another is akin to slavery.

The California bill will give all student athletes enrolled in public and private four-year colleges and universities in California the right to their name, image, and likeness, allowing them to earn money from sponsorships, endorsements, and other activities related to their hard work and talent—a right that all other students and California residents have, says the legislation.

It would prohibit colleges from enforcing NCAA rules that prevent student athletes from earning compensation. Receiving income would also not affect a student’s scholarship eligibility.

The bill had bipartisan support, passing the state Assembly on unanimous 73-0 vote and winning final approval from the state Senate on a 39-0 vote before being signed by the governor.

Another argument is Fair Pay to Play kills amateurism. However, many former college athletes think a bill like this would help improve amateurism and make college sports that much more competitive in the long run.

“I have a soft spot for the value of a college scholarship, but over the last couple of years, I’ve taken a different stance to a certain degree because now I see how much money the NCAA has made off collegiate athletes and they’re not able to see any of those funds,” Antoine Walker, another former McDonald’s All-American who won an NCAA championship, NBA championship, and who was the cover athlete of an NBA basketball video game, told The Final Call.

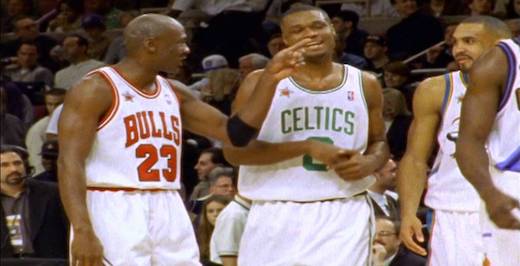

Former NBA player Antoine Walker (c) with Michael Jordan and Grant Hill. Antoine Walker was a former college basketball star and NBA champion. He values college education for athletes but argues they should also be allowed to make money while pursuing their education. Photo: Youtube

“I don’t think allowing college athletes to make money in this way will hurt the NCAA because people love college sports, and this can only make it better. In basketball for example, these schools bring in, sometimes three or four future pros every year and they only compete for one year before they turn pro for financial reasons because they have to take care of their families,” said Mr. Walker.

“But what if they could’ve made money off their likeness in school? They might have stayed. Fans could’ve gotten a chance to see them play for another year. That brings in more money for the school and the NCAA.”

Ed O’Bannon agrees. “If a college athlete signs an endorsement deal, won’t he or she be more likely to attend class, since if their grades fail, they’ll be kicked off the team and they’ll lose their endorsement deal? Also, won’t college athletes be more inclined to stay in college since they are gaining from endorsements while there,” O’Bannon said in Sports Illustrated.

The Fair Pay to Play Act has nothing to do with athletic scholarships. It wouldn’t take a dime away from schools. It’s all about the relationship between college players and companies that would like to pay for their endorsement or sponsorship, state supporters of the legislation.

Julius Hodge echoed the sentiments of Ed O’Bannon, Antoine Walker and the Gonzalez twins, and expounded on it saying, a move like this actually helps these student athletes become better business people; especially as they navigate and maneuver through the world of high-stakes sports and athletics.

“I think the NCAA should look at it this way: you can have a young student athlete learning the world of business and how to be business savvy at 18-years-old. This would really introduce them to the real world, as opposed to taking a stance that something like this is hurting amateurism of collegiate sports,” said Mr. Hodge. “The NCAA could look at it as we’re helping our student athletes to be their own business owners. That’s something they could learn that will help them for the rest of their lives,” he added.

Gov. Newsom signed the bill on “The Shop,” a television show hosted by NBA superstar LeBron James, who supports the bill. As a basketball phenom in high school, Mr. James states if he would have played college ball, neither he or his single mother would have reaped the financial benefits a university and others would have made from his image.

“Me and my mom, we didn’t have anything,” Mr. James told reporters. “We wouldn’t have been able to benefit at all from it. And the university would’ve been able to capitalize on everything that I would have been there for that year or two or whatever,” he added.

“I understand what those kids are going through. I feel for those kids who’ve been going through it for so long, so that’s why it’s personal for me,” he added.

The Fair Pay to Play Act won’t become effective until 2023. In that time, it’s unclear how many more states will pass similar laws, especially since the NCAA would be barred from banning member schools and their athletes from competing as a result. But two things are certainly clear. The first is the NCAA business model will never be the same. The second is the attitude and mindsets of college athletes have been changed forever because for the first time, they finally know how much they’re worth and they’re ready to cash in.

(Final Cal staff contributed to this report.)