By Bryan 18X Crawford | Contributing Writer | @MrCraw4D

The life, death and legacy of Nipsey Hussle not only deeply touched those who live in his Crenshaw community and the Greater Los Angeles area, but people across the country and around the world were mourning the 33-year-old man whose work in the streets and the suites was inspirational, and rooted in a commitment to build and help his people make progress.

Ermias Joseph Asghedom was seemingly born to be a bridge that connected people to worlds that seemed distant and in some cases, carried warning signs that read, “Do Not Cross.” The distance might have been as far away as the Horn of Africa or as close as blocks that surrounded the house where he grew up.

Born in 1985 to a Black mother from South Central Los Angeles, and a Black father from Eritrea, a country situated on the Red Sea in East Africa, Nipsey carried the DNA of a revolutionary, in his genes. His father, Dawit Asghedom, fled his home country in the midst of war where the combatants’ faces all looked the same, and landed in the U.S. where he would become politically active. In 1975, Dawit was photographed in New York City holding a sign that read, “Down With Apartheid and Imperialism.”

A decade later, his second and youngest son would be born in a place fighting a similar war in which the combatants’ faces, once again, all looked the same, and the son would embody a fearless spirit opposed to oppressive forces in South Central Los Angeles.

The name Ermias is Hebrew and when translated means “Sent by God.” A cursory look at Nipsey Hussle’s life, his works and response from the Black community and Black world in the aftermath of his death seems to bear witness to the meaning of his name.

Nipsey was born and raised in Crenshaw which is controlled by the Rollin 60s Neighborhood Crips; a community that is basically bordered on all sides by rival factions of the Bloods street gang. He joined the group. However, despite being affiliated with the Rollin 60s, unlike most members of Los Angeles street gangs, Nipsey was able to move, relate and associate seamlessly with those who were, by street code, the opposition, with essentially no beef—something unheard of in a city where having the wrong color rag (bandana) could lead to dire, and sometimes fatal consequences. He collaborated with artists in “rival” gangs and in media interviews talked about how he and others in Los Angeles built intentional relationships across gang color lines to keep conflicts out of the music and provide an example of how to enjoy mutual respect and mutual success. Those relationships went beyond Los Angeles and spread to other parts of the country as he toured to pursue his music and business ventures.

“If he met you, you were his people. That’s how he made you feel, and we don’t have a lot of people in this rap game who are like that. That’s why nobody is saying anything bad about Nipsey,” Terrance Randolph, a Chicago-based social media brand manager and influencer, known in the hip hop music industry as Hustle Simmons, told The Final Call. “I don’t know what purpose God had for his life, but he must’ve lived it out.”

By the time Nipsey Hussle was 14, by his own accounts, he had left home and begun taking care of himself, hustling on the streets of Crenshaw to survive. By the time his rap career had begun to take off and people started to recognize his name, acknowledge his talent and respect his art, Nipsey made sure to let everyone know, as the lyrics of one his songs go, he was a man with a different thought process, personal blueprint and unlike the usual “rap n****s” in the game.

“[We had a] real war in the streets. It was heavy. We were knee-deep into something real and it was about surviving and defending our opportunities,” Nipsey said in a 2018 interview with Mass Appeal. “I’m conscious that there’s an intentional pushback against people that look like me. I’m supposed to be in jail or dead. There’s a whole prison complex [that exists.] Then, you think about as an artist, there’s a business model that exists in the music industry that prevents you from having ownership; that prevents you from being a partner in the lions’ share of the profits. … When I said I was the Tupac of my generation, Pac was intelligent, but in our culture—street culture, especially in his generation—intelligence is viewed as weakness. So, how do you get the people affected by what we’re really trying to solve, involved?”

For Nipsey, the answer was being an example of what Black ownership meant and looked like, which in itself, was a game changer, especially for those from his community. With family and partners, he purchased the strip mall where he once sold CDs out of a car trunk, opened businesses, advocated for children and created a shared work space for techies in the hood.

According to media reports, there were over 101 million live streams in the two days after Nipsey’s March 31 passing. Streaming and purchasing the music benefitted, was encouraged because of the income directly benefits his estate. Victory Lap, his latest album, sold 64,000 copies the week of April 1. Other popular songs that were streamed included: Racks in the Middle featuring Roddy Rich and Hit-Boy (11.8 million); Dedication featuring Kendrick Lamar (9.6 million); Double Up featuring Belly and Dom Kennedy (8.5 million), Last Time That I Checc’d featuring YG (7.1 million) and Hussle & Motivate (2.9 million.)

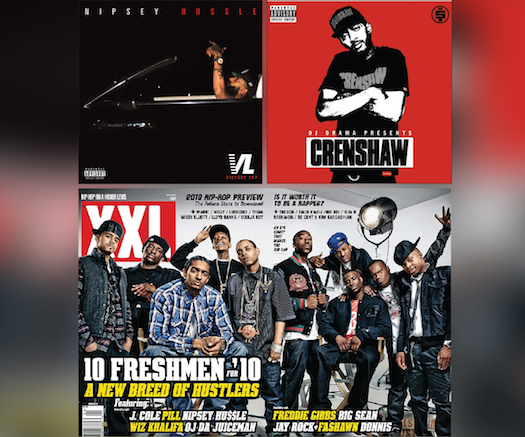

The proud West Coast rapper began his career in the mixtape circuit, selling his albums from the trunk of his car in Crenshaw. They were a success and helped him create a buzz and gain respect from rap purists and his peers. In 2010, he placed on hip-hop magazine XXL’s “Freshman Class of 2010”—a coveted list for up-and-coming hip-hop acts—alongside J. Cole, Big Sean, Wiz Khalifa and others.

Jay-Z even bought 100 copies of Hussle’s “Crenshaw” for $100 each in 2013, and sent him a $10,000 check.

Nipsey, once signed to Sony’s Epic Records, hit a new peak with “Victory Lap,” his critically acclaimed major-label debut album on Atlantic Records that made several best-of lists last year, from Billboard magazine to Complex.

At this year’s Grammy Awards, “Victory Lap” was one of five nominees for best rap album in a year that saw hip hop dominate the pop charts and streaming services, and debates ensued about which rap albums would get nominated since a number of top stars released projects, including Drake, Eminem, Kanye West, Nas, J. Cole, Nicki Minaj, Lil Wayne, Migos and DJ Khaled. Cardi B’s “Invasion of Privacy” won the honor in February, while the other nominees alongside Nipsey were Travis Scott, Pusha T and Mac Miller.

Touching South Central, America and the world

With his passing, his revolutionary and inspirational spirit traveled beyond the borders of the Crenshaw district, Greater Los Angeles, and touched Black communities throughout the U.S., and as far away as Africa and Canada.

“We have to move and act as a fraternal organization, as businessmen, and people that care about our communities and make an actual investment like Nipsey did,” said rapper Killer Mike at a Nipsey Hussle memorial vigil held in Atlanta just days after his death.

Killer Mike added, “We have a choice. We don’t have to be nobody’s savages. We don’t have to be their examples of the wrong way [to go]. We gotta be no thugs that’s been thrown away. That rag that’s over your forehead or [hanging] out of your left pocket, is better served wiping the sweat off your head for the work you’re doing on behalf of your community in a way that does not murder other Africans.”

“A sucker took out a king. … A real king to this era,” said Harlem-based rapper Dave East for an impromptu memorial gathering he organized to commemorate the life of Nipsey Hussle. “I was a kid when Big and Pac died, so I couldn’t feel that. I feel this. … Don’t let his name die.”

Other vigils were held in Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, Birmingham, Philadelphia, Milwaukee, San Diego and as far away as Vancouver, Canada,

In Houston, more than 1,000 people gathered in the Midtown section of the city, at the behest of Houston-based rapper Trae The Truth, all clad in Blue, to release balloons in honor of the slain star.

“Some people loved him for the person he was, some people loved him for his music. But regardless, people loved him as a partner, as a brother, as a father. Anything he was, he gave it his all and it was genuine. And these days, you don’t find too many genuine people,” Trae The Truth told NBC News affiliate KPRC in Houston.

T.I., another Atlanta-based rapper, took to his Instagram Live account to talk about Nipsey and take questions from his fans. Nipsey, who had a reputation in the hip-hop community for being both studious, and an avid reader, was known to gift books to people. When asked what book Nipsey gave him to read, T.I. answered, “Message to the Blackman by Elijah Muhammad.” Nipsey’s respect for the Nation of Islam isn’t something that was widely known publicly, but he never shied away from it. He, along with his friends, once famously threw rocks at the Los Angeles Police Department in defense of Student Minister Tony Muhammad of Mosque No. 27, who showed up after a young man was killed in Nipsey’s Crenshaw neighborhood.

“I remember some years back, one of our close friends from our area got killed and [Min. Tony Muhammad] came on 10th Avenue,” Nipsey Hussle explained in video posted on Min. Tony Muhammad’s personal Instagram page. “The police had put a cover on the young man’s face, and the cover was going up and down. There was people who knew the young dude telling the [paramedics] that he was still breathing, that he was still alive. But they just sat there and let him expire on the scene. But Tony Muhammad showed up and represented our community and he stood up. But he ended up having an altercation with the LAPD, but people in our area and myself specifically, always respected him for that.”

Said Min. Tony Muhammad in the caption for his video post, “I will never forget our Brother, a Giant ‘Nipsey Hussle’, he stood up for me years ago when we had an altercation with the LAPD in his Hood! Now I will continue my work of bringing an end to the killings of each other, in his name.”

While the impact of his death hit hardest here at home, it also resonated and affected those of Eritrean descent who live here in America and Africans on the continent.

Kenyan rapper Khaligraph Jones went online and uploaded a freestyle video devoted to Nipsey Hussle.

In Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, candles were lit during a memorial service for the beloved artist. “With poems and speeches, Ethiopians have held an emotional farewell for murdered rapper Nipsey Hussle, whose roots in neighbouring Eritrea won him admirers in both countries,” AFP reported April 7.

“ ‘When we heard there’s an Eritrean rapper out there, we were fans before we heard his music,’ ” said Ambaye Michael Tesfay, who eulogized Nipsey at the event held in a darkened parking lot. “ ‘He was an icon for us,’ ” AFP said. Despite conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia before a peace pact last year, Ethiopians shared their pride about Nipsey’s music and impact. “‘We’re all one people,’ ” Nemany Hailemelekot, who organized the gathering that drew hundreds of people, told AFP.

Eritreans paid their respects to Nipsey Hussle with many offering their feelings via social media. Journalist Billion Temesghen tweeted April 1: “Ermias Asghedom AKA Nipsey Husle was an Eritrean rap star, a preformance phenomenon, who had just returned home. In my pleasant talk with him I was delighted to learn of the Eritrean & African pride he carried deep inside him. He is a legend. compassionate compatriot. We miss him.”

“#NipseyHussle stood for #Eritrea when he was alive & he is still standing from heaven. His life is reinvegorating Eritrean youth to follow his footseps to stand for country &people despite all enmity thrown at them. Nipsy is rendering all anti-Eritrea campaigns mute. Rest in P,” tweeted Amanuel Biedemariam, who often writes for an Eritrean website.

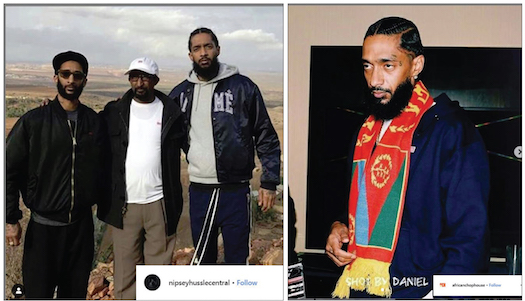

Nipsey’s two visits to his father’s native homeland, once as an 18-year-old young man still trying to figure out who he was and his place in the world, and the second time as a recording star had a profound effect on him.

On his last visit to Eritrea in 2018, Nipsey was treated as a dignitary who seemed to understand who he was and what he represented, while being fully aware that he was both a voice and example for two distinct peoples with a long history of fighting against injustice and oppression, not just one.

When asked by Eritrean journalist Billion Temesghen to describe in his own words what hip-hop is, Nipsey Hussle’s answer was both deep, and profound.

“[Hip-hop is] a form of expression for young people who have so much to be told. It is a vocabulary, it is an art and it is a culture that originally was only of young people in America but now has gone global. The neighborhoods from where Hip Hop came out had unique environments and situations that made people search for a real and efficient form of expression. From police brutality to gang cultures, the riots, racial discrimination and more unique events that urged the growth of Hip Hop in terms of music and Hip Hop in terms of culture and identity.”

He added, “The story of Hip Hop is similar to that of Jazz. Music in America was an expression of our struggles; being black in America. And I, as an Eritrean American, I feel connected to this aspect of the African American history. My father is from Eritrea and we have always been in touch with our Eritrean ancestry and culture thanks to him. However, we still grew up in South Central LA all of our lives. So our exposure was to the culture of Los Angeles, which was gang culture. I was born in 1985 and grew up in the 90s. … All of the social issues that took place back then happened in our backyard.”

When asked what it meant to have roots and ties to a place that has experienced its own share of violent struggle in the fight for independence, Nipsey’s answer poignantly encapsulated the parallels of life growing up in South Central Los Angeles, where the expectation for Black men is a life that leads to death, not one that can garner the love, respect and admiration of millions all around the globe.

“I am proud of being Eritrean. The history of our country, our struggle and the underdog story, the resilience of the people and our integrity is something that I feel pride in being attached to,” he said.

“He embodied Pan Africanism. He was a bridge between the two worlds of East Africa and the hood, which is really important,” former professor and Los Angeles native Kwame Zulu-Shabazz told The Final Call. “So, he was hood but also very Pan African, and he was proud of it. That’s something that we need more of, too. Part of the reason that we’re lost in the U.S. is because we’ve been disconnected from our roots, and brothers like that can help us reconnect and affirm that Africa is a positive place, and that there are positive things going on in Africa that can make us proud of our heritage as African people.”

His family and close friends, while understandably still mourning and trying to make sense of his tragic death, seem to all take some solace in reminiscing on the good things he did for himself and his family, but also the positive impact he made in the lives of others.

“He recognized at an early age his own capability. His own potential. He has always known,” Nipsey’s mother, Angelique Smith, said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “I would like for him to be remembered as a humble, spirited, respectful man who had, since his childhood, an extraordinary and unlimited intellectual capacity.”

Said his brother, Samiel “Blacc Sam” Asghedom in the same LA Times piece, “There’s a lot of politics within the area that we grew up in, but he stayed the course and showed what he was about. He made something work in an area that was run-down, that people were scared to come to, and he turned it into a landmark.”

Lauren London, mother of Nipsey’s two-year-old son Kross, told the newspaper that her fiancée, “was a protector and wanted us to be our best at all times. He was a truth seeker and truth speaker. I’m going to keep my head high and always represent for my king to the fullest.”

Dawit Asghedom remembered his son this way.

“It was like he was sent by God to give some love to bring us together because that’s what his lyrics were saying, always,” the elder Asghedom said, adding, “He’s not shy to tell the truth even though it might not look good. He wasn’t scared of anything. [God] sent him to send a message. It looks like, ‘Your time is up because you have completed what I sent you to do.’ We all have a plan, but God has his own plan. So he had completed what he needed to be doing and he did it early so [God] probably wanted to take him early too.”

From buying up the block, to creating businesses that employed Black people, aimed to educate them, and give them a space to be creative and help develop and realize their dreams, Nipsey Hussle was a man of the people because he was a man who saw what their needs were and took it upon himself to do what he could to help provide opportunities and a platform for others, because at one point in his life, he was looking for someone to give him the same opportunities and guidance. His death has seemed to galvanize the Black community, and this was evidenced by the recent gang truce that happened in the wake of his death. Over the April 7 weekend, hundreds of Crips, Bloods, and members of L.A.’s various Hispanic gangs, all marched through South Central together, gathering in front of Nipsey’s Marathon clothing store and standing in solidarity with one another as brothers and sisters in the same struggle, committed to carrying on the legacy of independence and ownership, which was Nipsey’s messaging in the final stages of his young life.

“My recent music is about the reality of the business; the challenges of working for your own business and how to be a Black young successful entrepreneur,” he told Ms. Temesghen. “I want my music to be an inspiration of individual growth in the economic sector. That is the path I took as I grew up and I want to put it in music. My life is different from when I first came out as a teenager with expressions from the teenage perspective of young men in the streets. Now, as I grew older and became successful in music and business my perspective changed accordingly. And so my art evolved with it.”

Ms. Temesghen explained to Nipsey in their interview that Eritreans had translated his name in their native Semitic language of Tigrigna, to “Nebsi,” which means “self,” and in Eritrean slang terminology, loosely means “homie,” giving his name dual-meaning in the country among Eritrean people: “Self Hustle,” or the “Hustle of Homie.” Ironically, this dual meaning of Nipsey’s stage name in Eritrea, fits perfectly with who he was back in America: a self-hustling homie whose fearlessness motivated and inspired others to follow his lead and do the same.

At Final Call press time, a memorial service was planned for April 11 at the Staples Center in Los Angles, which holds 21,000 people. It was expected to be full.

(Final Call staff and the Associated Press contributed to this report.)