By Bryan 18X Crawford

The entertainment world, and the Black community at large, collectively felt the loss and pain of the tragic and untimely passing of 33-year-old West Coast hip hop artist Ermias Asghedom, known professionally as Nipsey Hussle.

“Neighborhood Nip,” as he was commonly referred to, was gunned down, shot multiple times on March 31 in the parking lot outside of his clothing store, The Marathon, located in the Crenshaw District of Los Angeles.

Nipsey Hussle owned the plaza where the business was located, which is situated near the intersection of Slauson Ave. and Crenshaw Blvd., one of the busiest in Los Angeles.

In the 1980’s Crenshaw was one of the most violent sections of L.A. due to the influx of drugs and gangs, most notably the Rollin 60s Neighborhood Crips.

The shooting occurred at approximately 3:20 p.m. PDT, a little more than 30 minutes after Nipsey sent an eerily cryptic tweet that read, “Having strong enemies is a blessing.”

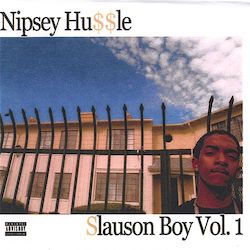

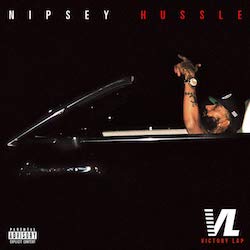

Born in 1985 in Los Angeles to an Eritrean father and a Black mother, Nipsey Hussle rose to prominence in the world of hip-hop in 2005 with his debut mixtape, “Slauson Boy Volume 1.” From there, Nipsey went on to release a bevy of underground mixtapes that quickly established him as next up in a long line of MCs from the Los Angeles area. Nipsey reached the pinnacle of his music career with the release of his “Victory Lap” album which was nominated for a Grammy in 2019.

However, in the process of rising up the ranks of hip hop, Nipsey seemed to find a bigger purpose that moved beyond just making music, and that purpose was giving back to the community that raised him and the people who helped shape him.

Businesses, buying property, independent building brands

Nipsey was widely seen as an authentic and relatable person and was true to his stage name.

He was a hustler in every sense of the word. And given the conditions of the Baldwin Hills-Crenshaw section of Los Angeles, he had to be in order to survive.

Crenshaw has a population of almost 31,00 people, 72 percent of them are Black, and seven out of every 10 people living in the area, are renters. In Crenshaw, the unemployment rate is double the national unemployment at 6.7 percent.

After leaving home at age 14 to begin living on his own, Nipsey learned to turn negatives into positives—and cold hard cash. Some stories are legendary.

In 2013, he made $100,000 selling 1,000 copies of his “Crenshaw” mixtape for $100, something that was unheard of, especially in an era where artists gave mixtapes away for free on the internet. Crenshaw sold out in less than 24 hours, with Jay Z, another rapper who made a name for himself in hip hop as a legendary hustler, buying 100 copies of the tape as a way to show his support.

Nipsey then took that money, created his own record label, and released another mixtape, “Mailbox Money,” under his All Money In imprint, pressing up just 100 copies with a price tag of $1,000 each. He sold 60 of them.

Just this year, Nipsey and his business partner, another Black man, purchased the shopping plaza where his clothing store was located. When he was younger, the owner of the plaza wouldn’t let area kids hang out around the stores. This angered Nipsey so much that he had a desire to one day own it.

And he did.

In addition to an upgraded version of his Marathon clothing store, Nipsey’s final vision was to add a barbershop, a restaurant, and fully redevelop the property into a six-story, mixed-use residential and commercial building, all in an area of town already going throughout extensive amount of development and change.

“This is us trying to disrupt retail, create a theme park for the brand. This is us trying to create a retail network to become vertically integrated. This is us trying to super-serve the core with an upgraded experience. This is us trying to fuse hip hop, fashion and tech,” he said of his vision for the shopping plaza. “So I think that we’re just putting our chips on experience. We think this is where retail is going. So we want to be one of the leaders.”

Last year, Nipsey and his partner in the real estate project, created Vector90, a 47,000 square foot co-working space, cultural hub and business incubator, featuring high-speed internet, conference rooms, tech training, and a professional development program and launch curriculum for startups. It also offers technology to neighborhood residents.

“Growing up as a kid, I was looking for somebody—not to give me anything—but somebody that cared. Someone that was creating the potential for change and that had an agenda outside of their own self interests,” Nipsey said at the Vector90 launch. “In our culture, there’s a narrative that says, ‘Follow the athletes, follow the entertainers,’ and that’s cool. But there should be something that says, ‘Follow Elon Musk, follow [Mark] Zuckerberg,’” he told Forbes magazine.

Nipsey also launched “Too Big To Fail,” a STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) program for youth in Crenshaw that he wanted to turn into an academy situated in the same space as Vector90. Ultimately, Nipsey had planned to take the program to other cities, including Atlanta, Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

“I remember feeling, like … Maybe I’m tripping. Maybe I’m not even supposed to be ambitious; maybe I’m not even supposed to be thinking this big and thinking outside the box. That’s a dangerous thing,” Nipsey said in a Forbes interview, explaining the thought process that led into the creation of Too Big To Fail. “I would like to prevent as many kids from feeling like that as possible. Because what follows is self-destructive.”

Nipsey was an early pioneer and investor in cryptocurrency since 2013. Believing that Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency were on their way to mainstream adoption, he invested in Follow Coin, a crypto company based in Amsterdam.

“Because this currency is not linked to central banks. It’s unregulated. That means a lot for the power structure that exists now,” he explained. “People that’s in power—the central banks, these fiat currencies that are traded globally—they got influence over the messaging and the narrative in the media. When you see people on Fox and traditional investors saying, ‘Don’t invest. Don’t put your money in these coins,’ that’s not actual financial advice. That’s political rhetoric.”

Nipsey gained quite a bit of notoriety for not only his business sense, but the many ways in which he was committed to leveraging all that he knew and learned, by giving back.

He used money earned from his rap career, combined with his business acumen, and charted a course toward creating a blueprint to generational wealth that other Black people could follow.

“Nipsey Hussle was very rare. There aren’t too many successful, young Black men who have dedicated and committed themselves to uplifting their community. His is an irreplaceable loss because we don’t often get that kind of a brother in the hood very often,” Dr. Kwame Zulu Shabazz, a former Knox College professor who was born and raised in Inglewood, just a few miles from the Crenshaw District, told The Final Call.

“He had the potential for being a revolutionary model for what Black people could do. A lot of people, when they get successful, they try to get out of the ’hood. But Nipsey stayed in the muck and mire of the wilderness, trying to do something different. He had the potential for greatness and was on the path towards that, he just got caught up.”

“Nipsey was one of us. He was for us. It’s rare that you get those rappers who are for us; the people,” Terrence “Hustle Simmons” Randolph, a music industry veteran in the areas of social media marketing and brand management, who knew Nipsey Hussle, told The Final Call.

“This is definitely one of those Tupac and Biggie moments, not just in music, but in Black history. The one thing Nipsey had that a lot of rappers didn’t, was the ears of the young people. The people who were willing to sit down, listen and learn something. He was telling them about entrepreneurship. He was teaching them about Dr. Sebi, which a lot of them didn’t know about. He taught them how to stand for something. He taught them that it was cool to make your money and then come and buy back the block. He spoke about economics. He made it cool to love your girl and be out in the public with her, holding hands. He was about family in an era of men jumping from woman to woman.

“And, he was Eritrean. For him to be of true African descent, and from South Central LA, and to see him do all the things he did, his loss, we feel that. It hurts.”

“This is terrible loss for the hood because he’d really tried to pick us up with him on his rise to the top,” Mr. Shabazz said. “But we need to follow his example and try to carry on as best we can. Nipsey laid out a road map, and he has a legacy, and hopefully we can use this galvanize ourselves and do something about the violence and try to continue on and honor his legacy… Nipsey should also be a reminder that there is so much talent in the ’hood, it’s just misdirected by design.

“But there’s lots of brilliance in the ghettos of the U.S. masked as lost potential. We just have to figure out how to harness and maximize that potential and not allow ourselves to become distracted by all this craziness out here.

“South Central is one of the oldest, and largest Black neighborhoods in Los Angeles, and Nipsey was well respected there,” filmmaker and LA resident Tariq Nasheed, told The Final Call. “He created business opportunities for the people, he gave a lot in terms of his time, his expertise in the world of business and music, he gave a lot of money to people; this guy was beloved throughout the whole community, and it transcended the different gang lines. Everybody loved this brother.”

Despite being a known Crip, Nipsey seemed to be immune from gang-related beefs involving himself directly, and he garnered respect from many associated with various factions of Bloods active in Los Angeles.

“I’m not the most well-versed in the Crips and the Bloods culture, but he was the type of person that gave so much respect to people, it made you have to give that respect back to him,” Mr. Randolph said. “That fact that Nipsey being a Crip and YG being a Blood, could work together and use their influence to get brothers to unite and see the bigger picture of what can be done by coming together, and the power associated with that, based on respect, was powerful.”

The pain of losing another Black man to gun violence, let alone one who in addition to being a talented musical artist, was also a forward-thinking visionary and entrepreneur, was palpable in the Black community; and not just in Los Angeles, but across the country.

Legendary Houston-area rapper Willie D, who rose to fame in the early 90s as a member of the group, The Geto Boys, was visibly shaken speaking about the slain hip hop artist.

“We talk about giving back. Here’s a man that made it out, went back, and helped as many people as he could,” Willie D said. “We are at war. We can’t afford to lose soldiers, especially the good ones. We gotta protect our soldiers at all costs ... Nip was solid, man. He was in the industry, but he wasn’t industry. He was self-made, loyal, consistent, just an all-around good dude. I don’t know what happened or what it was about, but I know ain’t no way Nip did nothing to deserve that.”

“There’s a cloud over the community right now. Everybody is extremely sad. The energy is off,” Mr. Nasheed said. “He was such a great dude; the kind who would give you the shirt off his back. He was very rare and you don’t come across very many people like that. And he was young. He was only 33, but he’d already accomplished so much.”

The Game, a Los Angeles native and well known rapper who was close to Nipsey Hussle despite their opposing Crip and Blood affiliations, recorded an emotionally charged Instagram Live post driving down Slauson Blvd. at 4 a.m., emotionally shaken over the death of his friend.

“I can’t sleep behind what happened to Nip, man,” The Game said. “I’m disgusted!”