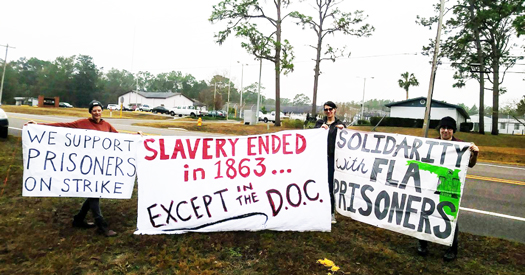

Supporters of Florida’s prison strike in January. Photo: @IWW_IWOCTwitter

Men and women behind bars in the U.S.—at great risk to their personal safety—began a national prison strike to protest inhumane living conditions, brutal and abusive prison guards and what they contend is modern-day slavery.

Representatives of the striking prisoners said inmates in institutions across 17 states are taking part in the strike action by refusing to work anywhere in prison buildings, kitchens, laundries and on prison grounds. Palestinian inmates have expressed solidarity and about 300 prisoners in Nova Scotia, Canada, joined the strike. The 19 days of peaceful protest was organized largely by prisoners themselves, said a spokesman for Jailhouse Lawyers Speak (JLS).

“Fundamentally, it’s a human rights issue,” read a Jailhouse Lawyers Speak statement released before the strike. “Prisoners understand they are being treated as animals. Prisons in America are a warzone. Every day prisoners are harmed due to conditions of confinement. For some of us, it’s as if we are already dead, so what do we have to lose?”

The strike which started Aug. 21 is organized by an abolitionist coalition that includes Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC), the Fire Inside Collective, Millions for Prisoners and the Free Alabama Movement. Jailhouse Lawyers Speak activists began preparing the action in April after prison officials in South Carolina put rival gangs in the same dormitory which ignited an outbreak of violence leaving seven inmates dead. (See Final Call Vol. 37 No. 40).

“We want to note that although there aren’t widespread reports of actions coming out of prisons, people need to understand that the tactics being used in this strike are not always visible,” said Jared Ware, during an August 22 press conference call. “Prisoners are boycotting commissaries, they are engaging in hunger strikes which can take days for the state to acknowledge, and they will be engaging in sit-ins and work strikes which are not always reported to the outside. As we saw in 2016, departments of corrections are not reliable sources of information for these actions and will deny them and seek to repress those who are engaged in them.

“We have spoken with family members who have suggested that cell phone lines may be being jammed at multiple prisons in South Carolina, and New Mexico had a statewide lockdown yesterday. The departments of corrections in this country are working overtime to try and prevent strike action and to try and prevent word from getting out about actions that are taking place.”

Prison guards oversee prisoners working in one of the gardens at C.Paul Phelps Correctional Center in DeQuincy, La., Aug. 8, 2010. Over 30 acres are farmed at Phelps growing vegetables for the 942 inmates. Photo: AP/Wide World photos

Mr. Ware, a freelance journalist who asked to be part of a team that coordinated with the press, said inmates organized nationally and carefully crafted the demands, strategically whittling them down from 35 to 10. The decision to strike, he said, was prompted by the deadly circumstances at South Carolina’s Lee Correctional Center, an understanding of how the state brings about the conditions of violence like that, and the types of changes that are necessary to prevent a repetition of that sort of violence.

“This is a human rights campaign and each of these demands should be understood through a human rights lens,” inmate representatives said.

The demands include:

An immediate improvement of conditions and the implementation of policies that recognize the humanity of men and women;

A greater investment in mental health services for prisoners;

Rescinding the Truth In Sentencing Act and Sentencing Reform Act to increase the possibility of inmates receiving rehabilitation and parole. No human should be sentenced to death by incarceration or no sentence should be imposed without possibility of parole;

An immediate end to prison slavery, with inmates paid the prevailing wage in their state or territory;

Rescinding the Prison Litigation Reform Act to give the incarcerated a proper channel to address grievances and rights violations,

An end to “racial overcharging, over-sentencing, and parole denials of Black and Brown humans.” In addition, “Black humans no longer (being) denied parole because the victim was White, a particular concern in Southern states.”

Although the United States represents one-fifth of the world’s population, 2.3 million people are incarcerated in America, the highest in the world. Estimates are that about 60 percent of that population is Black or Latino. Those numbers could ratchet up with Attorney General Jeff Sessions, at the behest of President Donald Trump, relaunching the failed “War on Drugs” and giving state attorneys and law enforcement the green light to crack down on criminal suspects even for non-violent crimes.

Prison reform advocates and critics of the criminal justice system note that the Prison-Industrial Complex is a multi-billion dollar enterprise which relies heavily on prison labor to work and produce goods and services for major businesses and corporations including Whole Foods, Starbucks, McDonalds, WalMart, Victoria’s Secret and AT&T.

The Prison Industrial Complex is a more than $2 billion enterprise, but many inmates literally work for pennies and others labor for free, said Dr. Kim Wilson.

“Exploitation of prison labor is at the heart of this strike,” said Dr. Wilson, a California resident and prison abolitionist. “Some people are making zero. I don’t want people to get the idea that it’s an at-will job. It isn’t a system where people have a choice to work. And nearer to the release date, you are expected and required to work.”

“At the largest wildfire in Mendocino County, thousands of inmates are fighting the fires. The reason is to save property. Prison officials try to sell the idea of this being rehabilitative but that’s not true.”

Dr. Wilson cited examples nationally of the work inmates are forced to do. In Angola Prison in Louisiana—often characterized as perhaps the most brutal prisons in the United States— inmates train and breed thoroughbreds and others pick cotton on the farm. Inmates in other institutions work on pepper and strawberry farms, she said.

“You also have prisoners building furniture for schools and universities, sewing Little League team uniforms and making military equipment, like helmets,” said Dr. Wilson, who has two sons serving life sentences at Vaughn Correctional Facility in Delaware. “This is not a small operation.”

Abdullah Muhammad, the Nation of Islam’s National Prison Reform Student Minister, said he hopes the strikes don’t end as tragically as it did at Attica in 1971 when prison guards killed a number of inmates. He added that he doubts how successful the strike will be because of the traditional recalcitrance of prison officials.

This Sept. 10, 1971 file photo shows inmates of Attica State Prison as they raise their hands in clenched fist salutes to voice their demands during a negotiating session with New York's prison Commissioner Russell Oswald. The whistleblower who spurred a major state investigation of alleged crimes and cover-ups at Attica prison is still on the case four decades later. Ex-prosecutor Malcolm Bell, now 82 and retired to the Green Mountains of Vermont, filed court papers in support of opening long-sealed investigation volumes. Photo: AP/Wide World photos

“I don’t think they’ll get all they’re asking for, and what they’re asking for will take money,” he said of the strikers. “These people don’t have it in them to raise the money and change the environment. They may get a program—in time.

“You can’t change the system. You always have what appears to be a change and what appears to be relief. For a moment. They wouldn’t be slave masters and oppressors if they did otherwise.”

Student Min. Muhammad said he’s struck by the symbolism surrounding the protests. Aug. 21 is the 47th anniversary of the murder of author, activist and Black Panther leader George Jackson, and Sept. 9 also marks the 47th anniversary of the bloody Attica prison uprising in upstate New York which is when the current strike is set to end.

He said he vigorously supports the idea posited by one of the strike organizers, Brother Rasaan, to “redistribute the pain.”

“The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., had a program that we (Nation of Islam) executed where from October to Jan 1, no money was spent in White businesses. A lot of people lost jobs, businesses suffered. That should be the program they implement,” said Student Min. Muhammad. The civil rights leader before his assassination suggested that Black people should “redistribute the pain” to White America through economic withdrawal in the demand for justice, a call reintroduced by the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan in 2015 leading up to the 20th anniversary of the Million Man March.

At the end of the day, though, Student Min. Muhammad explained, Blacks have no choice but to strike out and form their own nation. “We need our own land and territory,” he asserted.

Courtney Stewart is a prison reform advocate who was released from prison in 1985 and chairs the National Reentry Network for Returning Citizens in Washington, D.C. In his opinion, the prisoners who decided to strike had no choice.

“The thing is that these people, the corporations who make up the Prison Industrial Complex, have been getting away with murder for a long time,” Mr. Stewart told a Final Call reporter. “They’ve been able to sustain the Prison Industrial Complex and they have ruined generations and generations of the Black community. It’s been so devastating, and we still haven’t recovered.

“Using the school-to-prison pipeline and the ‘War on Drugs,’ these people are criminalizing and have imprisoned Black men, women and children. It’s profit over people and power and money in this capitalist, White-privileged society we live in. They don’t see any value in the Black family or Black people. They always throw pennies when it comes to fixing the African American community. We have to address this with force and radicalism. There has to be a radical revolution in how to address this.”

Mr. Stewart is not alone in the belief that the Prison Industrial Complex has to be dismantled and Dr. Wilson agrees.

“I’m a prison abolitionist. I see prisons as part and parcel of the problem,” said Dr. Wilson, co-host of a podcast called “Beyond Prisons” with Jared Ware. “I don’t know how they (prison guards) sleep at night. But those individual people are part of a larger system. I’m more concerned with the system as a whole.

“We want an end to the physical places we call prisons and conditions that make it possible in our society. But we can’t do that without addressing the underlying issues of racism, anti-blackness, capitalism, gender violence, ableism and other issues deeply implicated in the broader prison system. We must take seriously the things the prisoners are saying.”

Dr. Heather Ann Thompson has written extensively on the history of policing, mass incarceration and the current criminal justice system. She warned that the unrest, pushback and uprisings against the harsh conditions in America’s prisons will continue.

“I think that we have as a country been involved for so long in the ‘War on Drugs’ and the ‘War on Crime,’ that we have forgotten that it’s not normal,” said Dr. Thompson, a professor of history at the University of Michigan and the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and its Legacy.”

“But we have a whole generation of children for whom it’s normal to be pulled over, be arrested and shuttled into the system. We have been in a catastrophic prison crisis for decades now. And conditions have gotten even worse. South Carolina was a wake-up call for people,” she said.

“What cannot be understated or ignored is the fact that this is created and driven by racism. Seven point five million Americans are in the system. Most would not be here if they were the children of White lawyers, doctors and politicians. People turn a deaf ear to reform because White folks often don’t see Black children as children and think that Black people can absorb more trauma than they can.”

Dr. Thompson said she’s a White woman who grew up in Detroit and therefore, “My perspective is different. The situation is perfectly tenable as long as other people are being affected but when it becomes untenable is where White kids get caught up in the system. I give lectures and talks all over and the thing is that once they (Whites) really know what’s going on, they are appalled. They don’t know.

“Authorities cannot lock up 2.5 million people and have the trauma we have and it go on indefinitely. The incarcerated will continue to protest and people will continue to seek release,” she explained.

A strike organizer echoed Dr. Thompson’s warning. The inmate spoke with freelance journalist Brian Sonenstein, publishing editor at ShadowProof and a columnist at Prison Protest, in a story published in ShadowProof.

“No matter how many of these people they employ, it’s not going to take away from the issues and the problems of the violence that’s occurring inside the prisons,” said the inmate, a member of Jailhouse Lawyers Speak (JLS), which is a network of incarcerated self-educated legal advocates.

“What we’re dealing with consistently is prisoncrats refusing to accept responsibility, accountability,” said the inmate, who, fearing retaliation spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Because [they] created these conditions, these are the results. Instead, what they try to do is deny any responsibility, any liability, and say, we’re going to keep the same conditions while trying to force people to be subjected to those conditions. And how do we do that? We hire more employees.

“It never works. It’s not going to work. You can’t snuff out a human’s life without killing them,” the inmate said. “There’s gonna be some type of resistance.”