Wall Street and the wealthy profiting from police violence

BY BARRINGTON M. SALMON -CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Most American cities and counties routinely buy bonds to cover the millions of dollars needed for settlements and judgement costs after police killings and police misconduct. But in a twist that reflects the type of rapacious capitalism that now occurs regularly in this country, bankers and investors have been profiting from police violence.

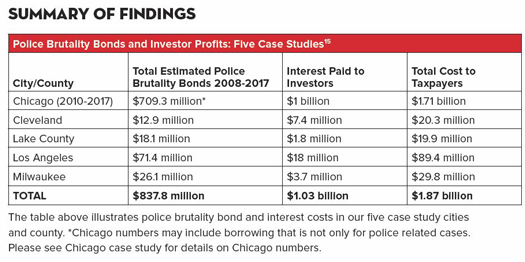

A report released last month by the Action Center on Race & the Economy (ACRE) Institute found that a number of cities and counties paid out $1.87 billion for what activists describe as police brutality bonds, and corporate titans like Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Goldman Sachs made more than $1 billion in profits for investors who buy these bonds.

ACRE is a social justice organization that has been fighting for structural change by directly confronting the financial elite they hold responsible for pillaging communities of color, devastating working class communities, and bringing harm to the environment. Activists say extensive research reveals that Wall Street investors have been profiting handsomely from police violence.

“Some of our nation’s largest corporate entities have made $1 billion in profits off of police violence,” said Maurice BP-Weeks, an ACRE co-executive director. “While we fight to hold violent officers and police departments accountable to our communities, we must also work to hold banks and investors accountable for their role in perpetuating and profiting from our existing system.”

Activists with ACRE are incensed, arguing that it is unconscionable that police violence and misconduct is wreaking havoc in communities of color and to add insult to injury, families are usually not fairly compensated, cities are straddled with debt and taxpayers are left holding the bag. Meanwhile, banks and investors enjoy the ill-gained profits. Mr. BP-Weeks’ colleague, Saqib Bhatti, agreed.

“Victims and their families deserve to be compensated. The payments they receive are a paltry sum for the harm they suffer at the hands of killer cops,” said Mr. Bhatti, co-executive director of ACRE and director of the ReFund America Project. “However, it’s unconscionable that banks like Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Goldman Sachs get a cut when a crooked cop kills an innocent Black person.”

ACRE activists said they call the bonds “police brutality bonds,” because they “quite literally allow banks and wealthy investors to profit from police violence. This is a transfer of wealth from communities—especially over-policed communities of color—to Wall Street and wealthy investors. Companies profiting from police brutality bonds include well known institutions, as well as smaller regional banks and other firms.”

The report released in June, studied the use of police brutality bonds in 12 cities and counties, ranging from mega municipalities like Los Angeles to smaller cities like Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. It includes five in-depth case studies of Chicago, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Cleveland, and Lake County, Indiana.

Researchers found that the targeted cities borrowed $879 million in bonds to cover police-related settlements and judgements which does not include the additional cost of interest paid to investors. Chicago is a perfect illustration of the problem.

Since 2004, city officials have spent more than $800 million on police-related settlements and judgements. Between 2010 and 2016, the city spent $360 million. During this same period, the city used $484.3 million in bond proceeds to pay for settlements and judgements.

ACRE researchers estimate that since 2010, big banks and law firms have made approximately $7.1 million in fees for underwriting the bonds authorized to pay for Chicago’s lawsuits. They also estimate that money borrowed by city officials will cost taxpayers more than $1 billion in interest that the city will pay investors over the life of these bonds.

Research from ACRE and elsewhere shows that the costs of police brutality, police-related killings and misconduct are rising and have not served as a deterrent because only a fraction of police officers or departments are ever held liable for their egregious or murderous behavior.

Chicago rally against police shootings. Photo: Haroon Rajaee

ACRE activists said that at the root of borrowing for police-related settlements and judgements is a one-two punch of inadequate revenues to cover a city’s expenses, and the escalating costs of police violence. In some of the cases, research showed that there were one or two particularly large settlements that caused a fiscal emergency for the city, they said. In other instances, cities are habitually relying on borrowing to pay settlement and judgement costs that predictably exceed the city’s dedicated funding year after year. In some cases, the borrowing happened in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, when many cities struggled with greatly diminished revenues.

In addition to the public bearing the cost of police misbehavior, Chicago’s police misconduct settlements takes away money from public education, health care, money that could be used to strengthen communities, particularly Black neighborhoods which have suffered significant disinvestment under Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration.

As the researchers note: In 2012, Chicago closed half of its mental health clinics, including four of the eight clinics on the city’s heavily Black South Side. Disinvestment from mental health services pushed more people into the criminal justice system and resulted in more contact between police and mentally ill people, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Similarly, they added, disinvestment in public education contributes to the ‘school to prison pipeline,’ resulting in more people getting caught up in the criminal justice system.

Another way Black people are affected is because disproportionate numbers of them are killed by the police and stopped and searched in higher numbers.

Again, Chicago. The Police Accountability Task Force, which was created after Laquan McDonald was shot 17 times by a police officer, found that 74 percent of those injured or killed by Chicago police shootings were Black men and that police disproportionately used Tasers against Black people. The taskforce report also found that CPD’s own data gives validity to the widely held belief the police have no regard for the sanctity of life when it comes to people of color.

“There is deep and long-simmering anger not just about McDonald, but the deaths of others at the hands of the police, including Rekia Boyd, Ronald Johnson and, more recently, Quintonio LeGrier, Betty Jones and Philip Coleman,” the taskforce report authors said. “The deaths of numerous men and women of color whose lives came to an end solely because of an encounter with CPD became an important rallying cry. That outrage exposed deep and long-standing fault lines between Black and Latino communities on the one hand and the police on the other arising from police shootings to be sure, but also about daily, pervasive transgressions that prevent people of all ages, races, ethnicities and gender across Chicago from having basic freedom of movement in their own neighborhoods.”

City officials have bought $709.3 million in police brutality bonds and taxpayers have been forced to pay a total of $1.71 billion.

LaQuan McDonald was shot and killed by Chicago police.

Cleveland is another city with a rogue police department that operated under a consent decree in 2004 and again in 2015. A Cleveland Plain Dealer investigation reviewed 70 lawsuits filed against the police in the previous decade that had resulted in taxpayer-funded payouts. The claims against the department align with Department of Justice findings that included allegations of excessive force, wrongful arrests and needless escalation of violence. Between 2008-2017, the city has paid $12.9 million in police brutality bonds at a total cost to taxpayers of $20 million.

The activists and researchers slammed one particularly corrosive element of capitalism that has become so commonplace.

“This wealth transfer is a feature of a financialized economy, in which the financial sector—or Wall Street—finds a way to extract profit from every facet of our lives,” the report’s researchers explained. “This process is known as financialization—the expansive control of the financial sector over our economy, our political system, and our lives. Financialization manifests itself as banks, hedge funds, private equity firms, and other financial institutions finding ways to profit from every possible aspect of our lives and using debt and wealth extraction as key ways in which to do so.”

Economist Mike Konczal at the Roosevelt Institute writes, “At its core, financialization is about reworking the real economy, the government and ourselves to serve financial needs. Financialization works to concentrate wealth and power at the very top of a racialized social and economic hierarchy. Wealth extraction in a financialized economy is not color blind, but targets communities of color in particular. ACRE activists are clear about what their long-term goals are.

“We need to dismantle this system of policing and build a justice system that prioritizes the needs and well-being of all people,” they said. “But until then, we will continue the work of fighting to hold violent officers and police departments accountable to Black and Brown communities and to curb abusive policing.

“We must also work to hold banks and investors accountable for their role in perpetuating and profiting from our existing system. Police violence should never be a source of profit for banks or investors, or a reason we do not have the resources we need to invest in the infrastructure and services that make our communities safer and more livable,” they said.

They offer several key recommendations, including that if cities must borrow money for settlements and judgements, banks and investors should not be allowed to profit from that. Banks who hope to do business with a city—such as by providing bond underwriting services, or other financial services—should be required to provide no-fee, interest-free loans when that city needs to borrow money to meet police-related settlement or judgement costs. Banks who refuse to do so should be barred from doing business with the city.

Police officers must be forced to take out individual liability insurance policies to cover the costs of settlements and judgements caused by their misconduct, said researchers.

“Officers whose behavior results in multiple misconduct claims will see their insurance premiums rise, creating a strong financial incentive for them to change their behavior. If they do not and the claims continue to rack up, they will eventually be uninsurable and therefore unemployable,” they said.

“It is an emergency. Until we radically transform America’s policing system, we need interim fixes that create incentives for abusive officers to change their behavior and force cities to remove officers who won’t change from their police departments. Requiring officers to carry individual liability insurance would force the hands of police officers and police departments alike, without draining money from public budgets.”

During their research, ACRE researchers said, there was, in most cases, a striking lack of transparency and disclosure around cities’ reliance on borrowing.

“And in every case study, there is a lack of full, accessible accounting of the costs. Most cities in our sample were unable, or unwilling, to provide a full accounting of how much they are spending on borrowing for settlements and judgements,” they said.

Therefore, governmental bodies at the local, state, and federal levels must account for and provide full transparency about which officers are behaving in ways that lead to settlements and judgements, how they are or are not being held accountable, who is paying for their misconduct and how, and who is profiting from these payments.

“There cannot be true accountability without transparency,” they said. “Cities must make data regarding claims against officers or the police department easily accessible to anyone who wants to see it by putting that data on a public website. They also must do a full accounting of the costs of settlements and judgements, including borrowing-related costs such as issuance fees and interest.”