Promoting Peace In The Streets - A long road to progress

By Richard B. Muhammad, Charlene Muhammad and Michael Z. Muhammad |

What's your opinion on this article?

National Urban Peace and Justice Movement leaders say 25 years of work still goes on

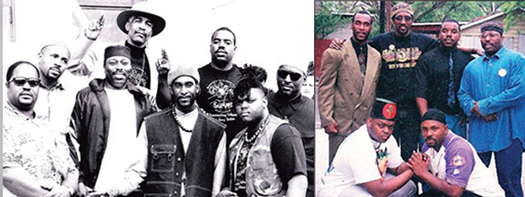

(L) Delegates to the 1993 Kansas City Gang Summit, including the late Omar Ali-Bey (center front), co-founder of the Coalition for A Better Life and Peace in the Hood. (R) Participants in the 1993 Gang Summit.

Twenty-five years ago, former gang members, activists and a few leaders pushed a movement to bring peace to besieged Black and Latino neighborhoods and demand justice for those stuck at the bottom.

Their efforts weren’t always welcomed. They were sometimes targeted by police agencies and their work is not often mentioned today.

But their efforts were proof that America’s cities didn’t have to be littered with bodies and bathed in tears.

The National Urban Peace and Justice Movement has now marked a quarter century of work. Some activists had gatherings like a summit held at Cleveland State University in June and another meeting is scheduled in August.

With Nation of Islam Minister Louis Farrakhan as a key supporter, with football great Jim Brown a major backer alongside then-NAACP head Ben Chavis and activist Carl Upchurch, a movement emerged in the public eye in 1993. Its first summit was in Kansas City, where then-NAACP director Chavis spoke, followed by other national summits in different cities.

Its agenda was ending fratricidal violence and giving young men and women alternatives to the world of drugs and crime. These new urban leaders also came from across country, literally from the West Coast to the East Coast and neighborhoods in between.

Peacemakers included Harry “Spike” Moss and Vice Lord leaders out of the St. Paul-Minneapolis, Minnesota area, the late Mr. Upchurch, then director of the Council for Urban Peace and Justice in Granville, Ohio, along with Prince Asiel Ben Israel of the Hebrew Israelite community, Earl King of No Dope Express and former street leader Wallace “Gator” Bradley in Chicago, the late activist Omar Ali Bey in Cleveland and others.

There were leaders in Los Angeles and California, where peace efforts between Crips and the Bloods spawned great hope.

1993 Gang Summit march in Kansas City, Mo.

Street organizations, activists, peacekeepers and gang interventionists participated in a unity gathering in July 2016.

Mr. Moss worked with students at a social service program called The City, Inc. in South Minneapolis. One day he noticed a lot of gang members were attending classes there. He worried about the rates at which they were shooting each other and decided they needed to unite.

He created a program called At Risk Youth Service to talk to as many children as he could and began connecting with street organization leaders.

He started in Minnesota, then Chicago, then Jim Brown, co-founder of the gang intervention effort Amer-I-Can, introduced him to leaders in Los Angeles.

By the time the Kansas City meeting was held, Mr. Moss had spent three years working the streets for peace, despite having guns pulled on him. Many didn’t want peace.

Student Minister Tony Muhammad with members of the Long Beach Crips during gang unity meeting at Mosque #27 in Los Angeles.

“They weren’t going to be with it because some enjoyed blood and murder, and some were making too much money off of drugs to let somebody interfere with their soldiers,” Mr. Moss said.

Consistency, determination, and fearlessness were needed, and Mr. Moss saw an example in Min. Farrakhan. He and other key organizers and gang leaders credit the Minister as a catalyst for the movement and for supporting its work—work that law enforcement, some political and other leaders condemned.

“There is fear in America over our young people coming together. I was told a few minutes ago that some members of the Minneapolis-St. Paul community offered money to some of the organizers of this summit if they would not let Farrakhan come. What is it about Farrakhan that you would offer my brothers money to keep me from talking to my own family?” asked Min. Farrakhan. “These are wonderful young people. They just need a chance and right guidance.”

With Minister Farrakhan keynoting the summit at Mount Olivet Missionary Baptist Church in St. Paul, Minnesota, on July 17, 1993, children and parents lined the sidewalks for two blocks, waiting for him, according to Mr. Moss.

“The other thing that was successful, and I give this credit to Minister Farrakhan, not just our hard work, but because he was willing to come, in a four-day period we registered 9,700 children, just because he was present,” Mr. Moss stated.

“When he came and made that address, you could hear a pin drop. But understand this, it was him, the great Jim Brown, Rap Brown (Imam Jamil Al-Amin formerly known as H. Rap Brown of the Black Panther Party and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee), Joseph Lowery, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Ben Chavis, Dick Gregory, Jesse Jackson, nobody told me no,” said Mr. Moss.

In 1995, these peacemakers would make an apology and appeal for peace at the historic Million Man March.

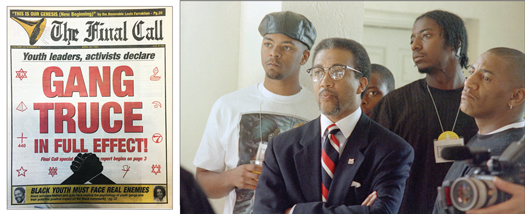

(L) April 26, 1993 Final Call issue (R) Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr., executive director of the NAACP stands among participants of the National Urban Peace and Justice Summit on Friday, April 30, 1993 in Kansas City, Mo. They are listening to Kansas City Mayor Emanuel Cleaver welcome them during the opening breakfast session.

Working to end urban warfare

If anything proved peace was possible, it was the 1992 gang truce between Los Angeles Bloods and Crips. Their battles had been deadly, devastating and depressing.

Gangs from four major housing projects in Watts Los Angeles—Nickerson Gardens, Imperial Courts, Jordan Downs, and Hacienda Village—forged an April 28, 1992 Peace Treaty.

Before that was a summit in Carson, Calif., in 1988, according to T. Dashiki Bey, also known as Twilight Bey, a former Bloods gang member. He is now an international activist for urban peace based in London.

“I was the one that shook my rival’s hand on television in 1988. I was the spokesperson for the delegation of Bloods and Crips at the Ramada Inn. I remember, very distinctively, the conversations that were had and I was 17 at the time,” Mr. Bey stated.

Most of the young men were in their late teens, and weren’t “shot callers,” but they agreed to take messages to leaders that things could be different.

“One of the primary reasons there was a need to come together because 1987-88 was the height of the gang war in L.A. We were experiencing about 1,000 to 1,100 murders a year and nobody was really winning the war that we were waging against each other,” explained Aqeela Sherrills, director of Resources for Human Development California, a gang intervention organization, in a 2012 interview with The Final Call.

“My basis for believing that that was possible was because we all went to school together,” recalled Twilight Bey. “But by the time we had gotten over the summer transition period from the 6th grade to the 7th grade, it was like we had been inducted and had been taken through a process and in preparation for this phantom war that was going to take place once we got to junior high school.”

Minister Farrakhan (c) presents several Latino members of the Nation of Islam to the gang summit held June 20, 2005 to broker peace in Los Angeles between Latino and Black street organizations.

Minister Farrakhan stands with mothers who lost children to street violence in 2004.

The next year Min. Farrakhan brought his Stop the Killing message to Los Angeles and there were meetings heavily attended by Bloods and Crips. He met with Crips and Bloods and the Black community at the St. Bonaventure Hotel on the subject of making peace.

When Los Angeles gang members announced peace efforts there was little applause and plenty of skepticism, Min. Farrakhan brought the Nation of Islam’s Saviours’ Day convention to Los Angeles in October 1993 as a tribute to the peace treaty between the Crips and the Bloods.

“My real reason for being here is to personally pay tribute and honor to Almighty God for putting his spirit in the Bloods and Crips who have initiated a truce by the power of God himself,” said Min. Farrakhan in his Saviours’ Day address. He saluted the young men and women for coming together despite “rivers of blood.”

Before Saviours’ Day 1993, there had been national gang summits in Kansas City, Cleveland, St. Paul, Minnesota and Chicago. But Bloods and Crips meeting in Los Angeles at the home of Jim Brown with Minister Farrakhan were intense.

Youth who identified himself only as “Twilight”, left, and youth who identified himself only as “Twelve”, clasp hands at end of three days of talks between members of warring Los Angeles gang factions in Carson, Calif., July 29, 1988. Twilight belongs to the Bloods gang and Twelve is a member of the Crips. The group issued a call for jobs as an alternative to gang membership.

“You had soldiers looking at soldiers, people who had taken casualties on both sides,” recalled Twilight Bey. “People who had felt the taste, the bitter taste of deaths of loved ones—looking at one another, eyes filled with tears, and considering the possibility of a life without this violence and you know, it was a continuation of the work and it was a continuation of the desire for this to change,” recalled Mr. Bey.

Mr. Bey insists 25 years of peace work has not stopped—it’s just been unseen. Some of it includes weekly conference calls by the Urban Peace and Justice Council. It is comprised of leaders, activists and faith and community groups who were dispatched from the 1990s series of peace summits starting in Kansas, according to Mr. Bey.

They work on violence-connected issues, share strategies, and dissect policies, particularly relating to Black communities in the U.S. and abroad, he continued.

A major issue remains economic exploitation under the guise of criminal justice, added Mr. Bey, who is still doing work as a founding member of Amer-I-Can from the U.S. to the United Kingdom, which has seen its own spike in shootings and stabbings authorities say are gang related.

Rashad Byrdsong is founder and CEO of the Afrocentric Community Empowerment Association, which serves youth and families in Pittsburgh, Penn. “There’s been times over 25 years we’ve had to go to two steps forward, and go back one, so in regard to Cleveland I think that we met our goals,” he said.

“The main thing is, given the situation in the country, the re-emergence of a lot of homicides, killings and shootings and just how the country is today under (President Donald) Trump, there’s a lot of conditions and situations today that we didn’t find ourselves in 25 years ago,” Mr. Byrdsong said.

In Cleveland in 1993, a summit brought people together for workshops and successful panel discussions. The intergenerational interaction was great because adults often don’t talk to youth, noted Mr. Byrdsong.

The summits and conversations created an opportunity for organizers to cut through popular culture influence on youngsters through music, substance abuse, and other risky behavior made glamorous.

Iroc Avelli, an original member of the Rollin 60s Crips from Chino, Calif., was very instrumental in bringing Crips to the table, according to Mr. Moss. But Mr. Avelli also brought Bloods and celebrities too. He fell into gangs after he kept suffering concussions from football injuries in college. Now a celebrity bodyguard, he was part of most of the summits and spoke to youth across the country in churches and schools. “I would tell the kids why, if I had to do it all over again, I would have stayed with football, because my parents were civil rights activists,” said the Louisiana native. The work of the gang peace movement reverberated throughout the schools, especially after the first Kansas City summit, according to Mr. Avelli. “When asked after that first summit how y’all feel about it now, a lot of little kids said ‘hey, we’re going to listen to that. First off, I don’t want to be a gang member and be in school. I just want to stay in school.’ It affected so many kids, because they were getting it from the real,” Mr. Avelli said. He feels Mr. Moss deserves to be honored internationally for his courage, humanity, and integrity for his role in the movement.

Fear of peace and a Black army

(top photo) Rappers, The Game and Snoop Dogg led a group of men of the community, including street organizations, in a march to Los Angeles Police headquarters in 2016. (bottom photo) Juan Bogan, executive director, Church of Scientology Inglewood, rapper Problem, Danny Bakewell, executive publisher, LA Sentinel and LA Watts Times Weekender, rapper The Game, will.i.am of the Black Eyed Peas, NOI Western Region Student Minister Tony Muhammad, Big Boy of 92.3 REAL Beat, apl.de.ap of the Black Eyed Peas and Rev. Alfreddie Johnson. Street organizations were calling for peace an an end to police brutality.

The movement wasn’t all good news and kumbayas: After four to five years of momentum, several organizers, like Sharif Willis, had run-ins with the law. Mr. Willis, from Minnesota, was charged with possession of firearms and locked up. The once chief minister of justice for the Vice Lords did 23 years and seven months in jail. He has been out of prison for a little over a year and a half. His sentence was tied to drug and weapons charges stemming from a 1994 incident.

“They went back 25 years of my history in order to get enough prior convictions in order to give me 27 years in the federal penitentiary for a gun,” Mr. Willis said.

“My parole officer that I had said the efforts to get me off the streets were such that they believed that I was today saying ‘peace,’ but I was really trying to mobilize a Black army where I could at some point say, ‘let’s go to war.’ ”

Many returning from prison want to use their wisdom, knowledge and influence to help steer youth in the right direction, he said. According to Mr. Willis, plans are underway for a summit featuring legendary entertainer Stevie Wonder in Florida in late summer.

“A lot of brothers weren’t able to communicate with some of these young brothers and as a result, things went back to business as usual, if you will,” he said. “And a whole lot of disarray took place within the various organizations with guys being locked up or what have you and there not being any real leadership available to scold guys or redirect guys or apprise them of what their actual responsibilities were in relationship to the laws, policies, and rules of their particular organizations,” Mr. Willis said.

In Kansas City in 1993, there were Bloods and the Crips, Gangster Disciples, Vice Lords, Blackstone Rangers, Mexican Mafia and Texas Syndicate and others. Many participating groups were sworn enemies of one another.

Chronic conditions spark change

According to Wallace “Gator” Bradley, a former Chicago Gangster Disciples enforcer, and CEO of United In Peace, the killing of young Dantrell Davis in Cabrini Green in 1992 was a turning point. The child died during gang conflict in the public housing project. “We decided to come together to stop the violence locally then,” he told The Final Call. “There were peace initiatives throughout the country. Every city was having the same problem.”

The “urban translator” also later pushed leader Larry Hoover’s call for the Gangster Disciple nation to transform itself into Growth and Development, focusing on self-determination and changing the lives of young men. Mr. Hoover was transferred to a super-max federal facility, denied parole and law enforcement targeted leaders, claiming public safety concerns. There were gang crimes units that were often abusive and corrupt. Cops sometimes dropped gang members in rival territory, feeding retaliation.

El Hajji Khallid Samad, a Cleveland-based organizer, believes Almighty God, Allah, inspired people in different cities to get involved and network.

“The crack cocaine epidemic, serious cultural and social issues around morality, the incarceration rates were going up. Cleveland and several other cities were about to be labeled war zones by the UN. These were the hot-button issues,” he explained.

Some “civil rights leaders were interacting with more of the Black Power-oriented Muslim leadership to develop a strategy and out of that came a collaboration and coalition of faith and grassroots community leaders to put together an effort to reduce the violence,” he said.

“A decision was made to come to Kansas City because of its central location between the East and West Coast. It also had strong Black leadership,” Mr. Samad explained.

Leaders from street organizations, the Nation of Islam, Sunni Muslims, the Moorish American Science Temple, and the Hebrew Israelites joined together, said Mr. Samad.

“Mexican leadership out of both Northern and Southern California, who were at odds, also a large delegation of Hispanics from the Midwest and East Coast. On the day before the summit, Cesar Chavis died, and we all came together and decided to dedicate the summit to his life and legacy,” recalled Mr. Samad. “It increased the participation for the Hispanic community.”

“As soon as peace broke out in LA the violence in Watts, homicides, assaults went down. We tracked it. After we left KC, the murder rate dropped 25 percent to 30 percent. We knew we were on to something,” he said.

Mr. Byrdsong added, “In 1995-96 we had decreased violence in major cities in America. No one is telling that story.”

“At the same time, we were calling for reinvestment into these communities there was a counterintelligence program ushered in with the arrest of the youth for racketeering and the RICO Act, Bill Clinton and the conservative establishment was pushing three strikes and you’re out, minimum mandatory sentencing, crack versus powder cocaine” sentencing, he said.

The prison penalty for selling crack cocaine was 100 times higher than powder cocaine, but it was the same drug. Crack was more associated with the cities and powder more associated with Whites and the suburbs.

“As a result, the prison population continued to grow becoming today’s prison industrial complex, mass incarceration,” observed Mr. Byrdsong. “Very little went into social intervention. The brothers who put down the guns had to figure out how to eat.”

Philadelphia activist Bilal Qauum wasn’t part of the 1990s urban peace efforts but he was part of 1970s work to stem gangs in Philadelphia. He sees lessons to be learned from these efforts.

“The House of Umoja held a gang conference 1974 that led 80 gangs to sign a peace treaty called the Imani Pact,” he told The Final Call. “Folks don’t talk about it much anymore. We were averaging 90 gang deaths a year in Philly before the pact. That’s why today I believe we can make a difference. We eliminated gang deaths. I say we did it before, and we can do it again.”

Gangs, cliques and group ‘beefs’

Mr. Qauum and others say street life has morphed out of tight knit groups and into loose, smaller cliques. “The problem now is we don’t have gangs. We have groups of brothers that rumble with each other, but they are not gangs. We have beef among groups,” said Mr. Qauum.

Khalid Raheem, CEO of the National Council for Urban Peace and Justice in Pittsburgh, said, “Today gang structure is not what it used to be. There used to be more resources for outreach and to get guys to come to the table because they have had a sense of loyalty. Now it’s almost like each man or women are for themselves. There is a big difference between the juvenile gang mentality versus the urban gangster mentality. People who came together to defend their territory. Now it’s about selling drugs and they have no loyalty to anyone except for their pocketbook.

“We learned that anything is possible when you build unity. Being able to organize and mobilize people takes a tremendous amount of energy and usually occurs following some tragedy. You must organize based on solid principles and strategic thinking and planning,” he said.

El Hajj Khallid Samad, a longtime activist and Muslim leader based in Cleveland, was among those working the streets alongside mentor Omar Ali Bey.

In Cleveland, his International Council, Coalition for a Better Life, and Peace in the Hood, Inc. came together in June. The meeting was an anniversary commemoration connected with ongoing programs.

He was able to have some youth in the criminal justice system participate. “They haven’t let them kids come out to nothing except to go down to the big boys’ prison or go to court, because of all the riots and the fights that have taken place,” Mr. Samad said. “We didn’t have one incident. We didn’t have one argument.”

A conference highlight included dialogue with leadership from a major gang and its affiliated. They were very attentive, participated in discussions, and were enlightening, said Mr. Samad. Many youth under 25 have been subjected to intergenerational trauma, he said. They didn’t know anything about the summits, nor peace treaties while joining the gang, according to Mr. Samad. He noticed every male he talked to came from families inundated with drugs and households with no fathers. There was a Day of Remembrance and Healing for the Survivors and Victims of the Madness at the African American Cultural Gardens in Cleveland.

Organizers are working on a blueprint for furthering peace work and plan to meet during Pittsburgh’s Black Family Reunion in August, according to Mr. Samad.