SELMA and the real Dr. King

By Askia Muhammad -Senior Editor- | Last updated: Jan 13, 2015 - 6:17:36 PMPrinter Friendly Page

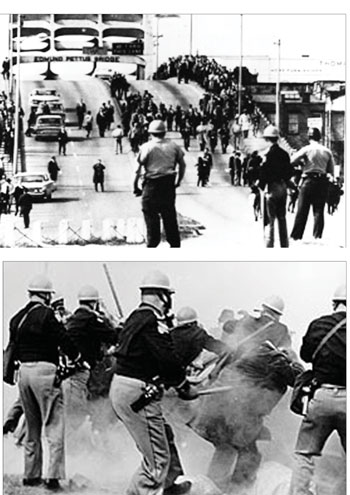

Martin Luther King leads march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, March 1965.

|

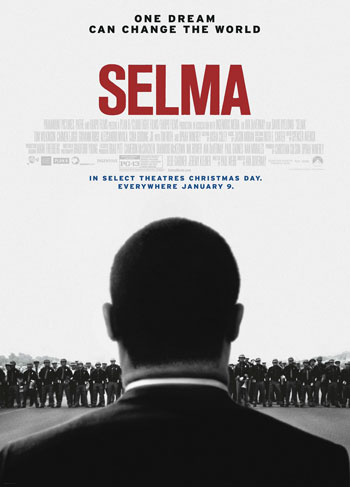

WASHINGTON (FinalCall.com) - The movie Selma is, and will likely remain, one of the most talked about films of 2015.

It earned four Golden Globe nominations, for: Best Picture; Best Actor, David Oyelowo as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; Best Director, Ava DuVernay; and won Best Original Song, “Glory” by John Legend and Common. And it is certain to be a contender for multiple Academy Awards as well.

|

Selma is an exceptionally well crafted depiction of the last successful campaign in the career of the most charismatic and possibly most misunderstood leader of the 20th Century Civil Rights Movement. It takes its greatness from portraying the tension caused by blood in the streets of Alabama in the mid-1960s brought on by violent, White-racist, legal and extra-legal resistance to the legitimate demands for the right to vote by Blacks in the South, and from the political push and pull generated from the teeming grassroots represented by Dr. King, all the way to the desk of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

The movie tells the story of three months in Selma, Ala., in early 1965 when Dr. King was mobilizing for the fight for voting rights. The bloody, one-sided “beat-downs” of peaceful, unarmed, non-violent protestors by vicious police, some on horseback, some with dogs, with tear gas, with billy clubs and other weapons, provokes a painful reaction to the scenes of the injustice and reminds moviegoers of the public moral outrage in 1965 which became massive public support for the passage of the Voting Rights Act by Congress later that year.

And while a great deal of “artistic license” is taken with the presentation of, or the exclusion of important Black figures in the voting rights struggle—Fannie Lou Hamer, Stokely Carmichael, Ella Baker, Floyd McKissick, among others—it is President Johnson’s screen role in the infamous Selma marches which has garnered the loudest rebuke.

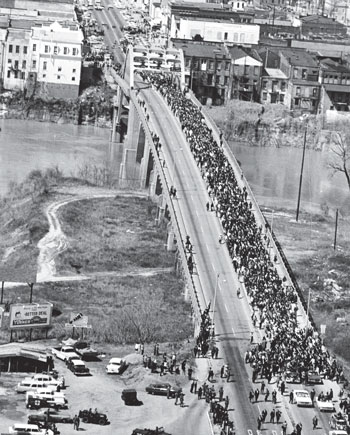

This March 21, 1965 file photo shows civil rights marchers crossing the Alabama river on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala. to the State Capitol of Montgomery. Photos: AP/Wide World photos

|

In the film, one dramatic climax occurs when Dr. King scolds the reluctant and tough-talking president, about the immediate need for federal voting rights legislation, all the while with a portrait of George Washington looking on in the background.

“Mr. President, in the South, there have been thousands of racially motivated murders,” Dr. King says, imploring President Johnson to put his weight behind a voting rights law. “We need your help!” But the President replies: “Dr. King, this thing’s just going to have to wait.”

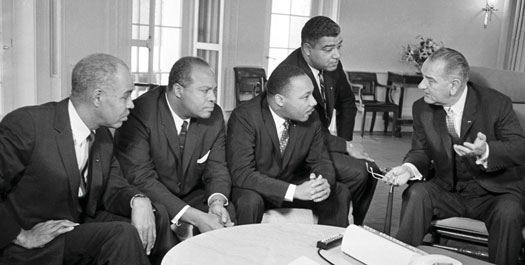

“In real life, that December 1964 meeting happened—but not that way, according to one who was there,” Richard Prince reports in his online column “Journal-Isms.”

“‘It was not very tense at all. We were very much welcomed by President Johnson,’ recalled former Atlanta mayor and U.N. ambassador Andrew Young, who attended the session as a young lieutenant to King. ‘He and Martin never had that kind of confrontation.’”

Others, including Clifford Alexander, a Black man and former deputy special counsel to the President, and later Secretary of the Army in the Jimmy Carter administration, as well as Joseph Califano, Mr. Johnson’s top assistant for domestic affairs from 1965-1969, and scholars at the Johnson Presidential Library cite transcripts and audio recordings in which Mr. Johnson appears to be the author of the idea of the Selma marches, encouraging them as a way to generate pressure on Congress to enact voting rights for disenfranchised Blacks.

State troopers swing billy clubs to break up a civil rights voting march in Selma, Ala., March 7, 1965.

|

While this film concentrates on early 1965 and Selma, one of the shocking early scenes shows the 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church—less than three weeks after Dr. King’s triumphal March on Washington for Jobs and Justice—in which teenagers Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley were blown to bits by a Ku Klux Klan bomb.

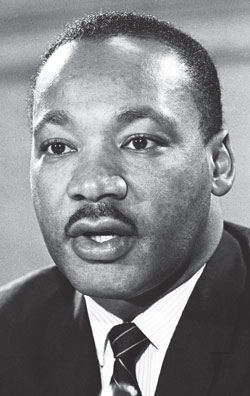

The film also shows Dr. King receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, but it omits much about the Black community which was the backdrop for Dr. King’s success, and more importantly the bolder, more militant Martin Luther King Jr.—The Real King, so to speak—who emerged during the three years after the Selma victory.

“There is no movement without the Black church. There is no movement without historically Black institutions. Not just colleges, high schools,” Dr. Greg Carr, chair of the African American Studies Department, at Howard University told The Final Call. “(The Revs. James) Bevel and (Fred) Shuttlesworth came back from Birmingham and said, ‘I’ve been going to the high schools talking to these kids. They’re ready to move.’ That’s when the Children’s March emerged.” Organizers were meeting at 16th Street Baptist Church, he pointed out, which is “Why they bomb(ed) 16th Street…because it was an institution.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., right, pictured in his first meeting with Elijah Muhammad, left, head of the Nation of Islam Feb. 24, 1966, in Chicago, IL. Dr. King said Elijah Muhammad agreed a movement is needed against slum conditions.

|

Those details and others depicting important local leaders were conveniently scrubbed from the film. “The politics of the film, the intent of the politics of the film were clear in the erasure of Stokely Carmichael, total erasure. The diminished capacity that is the role of Diane Nash and other women, the anti-SNCC perspective was just so clear,” Dr. Jared Ball, Associate Professor of Communications at Morgan State University told The Final Call. “John Lewis is a hero (in the movie), not just because of what he did but because he walked away from SNCC.”

The film, very skillfully diminishes the role of young Black militants who increasingly began to influence Dr. King in and after the events at Selma, in favor of the need for the movement to capitalize on a sense of White conscience and guilt.

But the reality is that conditions on the ground were changing fast in 1965. The Voting Rights Act was signed into law by LBJ in Washington—with Dr. King at his side—on Aug. 6, 1965. One week later, a continent away, the Watts Riot (rebellion) broke out on Aug. 13, protesting police murders and brutality toward Black people, like the 2014 demonstrations in Ferguson, Mo., and Staten Island, N.Y.

“That LBJ, is made to look almost heroic (in the movie) in juxtaposition to George Wallace, and could get—in the theater where I saw it—a round of applause, tells you where the film was asking us to go. The emphasis on the inter-racial aspect of the movement was a clear message of, ‘let’s walk away from Black collective national activity, let’s make a point about today,’” said Dr. Ball.

“If you look at the critique that is all over the place of Whites in these anti-Ferguson, anti-police brutality rallies, the critique is still there. ‘Why are you in these rallies White folks? And what is your intent in marching with us? And how is your presence becoming theater for you, as opposed to a movement for us?’

“All of those questions—like there is a response in Selma (the movie) to all of that—by saying ‘They’re (Whites are) supposed to be here. There’s a benefit to their inclusion,’ and all of the arguments or debates against that have to be diminished, ridiculed, omitted entirely.’”

“The problem is, that I did like it,” Dr. Ball said. “I was moved by some of it. I did think it was well made, and some of the acting performances are good, which makes, the negatives have much more of an impact. That’s the problem that we deal with. If it was all whack, it would be easy to critique and dismiss.”

In this Jan. 18, 1964 fi le photo, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, right, talks with civil rights leaders in his White House offi ce in Washington, D.C. The Black leaders, from left, are, Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); James Farmer, national director of the Committee on Racial Equality; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; and Whitney Young, executive director of the Urban League. Photos: AP/Wide World photos

|

The “real” Dr. King emerges

In the months after the Voting Rights Act, Dr. King underwent a radical transformation. The influence of the Nation of Islam was clear. “At one time the Whites in the United States called him a racialist, an extremist, and a Communist,” Nation of Islam National Spokesman Minister Malcolm X said of the mainstream Civil Rights leaders he nicknamed “The Big Six.” “Then the Black Muslims came along and the Whites thanked the Lord for Martin Luther King.”

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Photo: AP/Wide World photos

|

The strategy, of which Dr. King and the Civil Rights leadership was so proud, had produced a “victory with no victory,” Minister Malcolm X declared of the successful tactic which produced no tangible results. In the film “Selma,” Dr. King even laments in a jailhouse scene that he may have been fighting to integrate lunch counters at which most Blacks could not even afford to eat.

The Whites, Minister Malcolm X continued, did not integrate the Civil Rights Movement, they infiltrated it.

On Feb. 23, 1966 Dr. King visited the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, at his home in Chicago, and may have been further radicalized, but he quickly explained to his anxious White benefactors and to the public, that he was not forging an “alliance” with the Nation of Islam. In 1966 Dr. King’s Chicago organizing campaign was violently rebuffed by racist, White citizen attacks. He left Chicago, unable to claim a victory.

April 4, 1967 the day when Dr. King explained why he was opposed to the war in Vietnam arrived. “He comes out in this speech and he calls America, his country, ‘the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.’ That’s a strong indictment. The greatest purveyor of violence in the world today,” radio and television interviewer Tavis Smiley told Pacifica Radio’s Mitch Jesserich in an interview before the release of Selma.

Police attack marchers as they crossed Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge on “Bloody Sunday”. Photos: MGN Online

|

“He goes on in that speech to talk about what he calls the ‘Triple threat of racism, poverty, and militarism. Racism, poverty, and militarism.’ If you think you know Dr. King and you don’t know of the story of the darkest and most difficult part of his journey—which for him just happened to be the last year, April 4, ‘67 to April 4, ‘68—if you don’t know that story, then you don’t know Dr. King yet.”

Mr. Smiley is the author, along with David Ritz, of “Death of a King: the Real Story of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Final Year”. During that troubled time, up until his assassination, Dr. King had become so unpopular that another author, Clayborne Carson said many of the people who went to his funeral, would not have been seen with him on the day before he died.

“Clayborne Carson is absolutely right,” Mr. Smiley said. “In the last year of his life, everybody and everything turned against Dr. King.

“After he gives his speech, the media turns against him. What The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Time magazine had to say about him, you would be embarrassed. So the media turns on him. Then the White House turns on him.” While President Johnson and Dr. King worked together for the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act—perhaps the two most seminal pieces of legislation passed in the entire 20th Century—now King is opposed to LBJ on this war in Vietnam, according to Mr. Smiley.

“The NAACP and Roy Wilkins turns on Dr. King. Whitney Young and the Urban League publicly turn on Dr. King. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., powerful Congressman, turns on Dr. King, publicly. Ralph Bunche, the only other Black Nobel Peace Prize winner, turns on Dr. King publicly. I can’t even say on the radio—it’s in the text—but I can’t even quote what Thurgood Marshall—The Thurgood Marshall—had to say about Dr. King. It was vicious and ugly.

Still from the movie “Selma”.

|

“And then the Black Press got in on it. It wasn’t just the mainstream, liberal, White press, the Black press started to turn on Dr. King. It’s a story most of us don’t know because we’d rather freeze-frame King at the Lincoln Memorial at the March on Washington.

“That dream that he talked about in ’63, by the time he gets to ’67, where this book picks up, the last year of his life, he is saying publicly that that dream has become a nightmare. He says to Harry Belafonte and a few others at a gathering one night, ‘…that for all that we have done for integration, I fear that we have integrated into a burning house.’ These are Martin’s words.

“The one that shocks most people: Martin was murdered on a Thursday night in Memphis. If he had made it back to Atlanta that Sunday to Ebenezer, his church where he was preaching every Sunday, his sermon would have been a shock,” continued Mr. Smiley.

On April 4, 1968, one year after his anti-Vietnam War speech, “One of the last calls he made from the Lorraine Motel was back to his church, to his secretary, to his father, to let them know what he was going to preach on Sunday. Had he made it back to Atlanta, his Sunday morning sermon was going to be entitled: ‘Why America May Go to Hell.’

“He didn’t say we were going to hell, but why America may go to hell. Now you tell folks that the ‘I Have A Dream’ man was going to preach a sermon called ‘Why America May Go To Hell,’ they don’t get that. King was always a believer that America could be greater. That’s what his life’s work was all about. But by the time he gets to ’67, ’68, he’s questioning whether or not America really has the will to address these issues that are really just threatening to the lives of too many fellow citizens,” said Mr. Smiley.

Ironically, the sentiment about the Vietnam War which earned Dr. King such unforgiving scorn is not unlike a prediction nearly 200 years earlier by Thomas Jefferson, one of this country’s Founding Fathers. “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever,” Mr. Jefferson said.

In order to get an idea of whom “The Real” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is Dr. Ball has a recommended reading list after having seen Selma. He recommends that people study the history recounted in the film, read Dr. King’s last book “Where Do We Go From Here? Chaos Or Community”, read James Forman’s book “The Making of Black Revolutionaries,” and read everything by or about Kwame Ture/Stokely Carmichael.